Articles / Help or harm: Could social media age restrictions backfire?

With the Albanese Government gearing up to enforce a minimum age for social media access, 95% of GPs agree restrictions are needed, a Healthed survey of almost 1500 GPs has found—but exactly what that should look like is less certain.

Sixty-five percent agreed with a ban outright, while a further 30% said restrictions are needed but did not agree with the government’s specific proposal.

Details are sketchy, but the legislation will draw on a report by former Chief Justice of the High Court, Robert French AC, which proposed a bill to ban children under the age of 14 from social media and require social media platforms to ensure parental consent prior to giving access to children aged 14 or 15.

Headspace, Beyond Blue, the Black Dog Institute, ReachOut, Orygen and batyr delivered a joint statement at parliament house, arguing that while research has clearly shown that social media is harming some young people, it also benefits youth mental health through peer support, information and a sense of community.

“In an already overstretched mental health system, we strongly advise against shutting off a free and accessible avenue for support that is helping young people understand what they are going through, validate their experience, connect with others and build their confidence to take action and then seek further forms of support,” the joint statement said.

“A ban would also expose young people to new harms. It may leave some young people without any mental health support options, it may make them less likely to seek help when they need it, and be less likely to tell an adult when things go wrong on social media. It may also push them from known online environments where we can offer support and implement reforms to improve safety – to other platforms of which we have no oversight or safety regulation.”

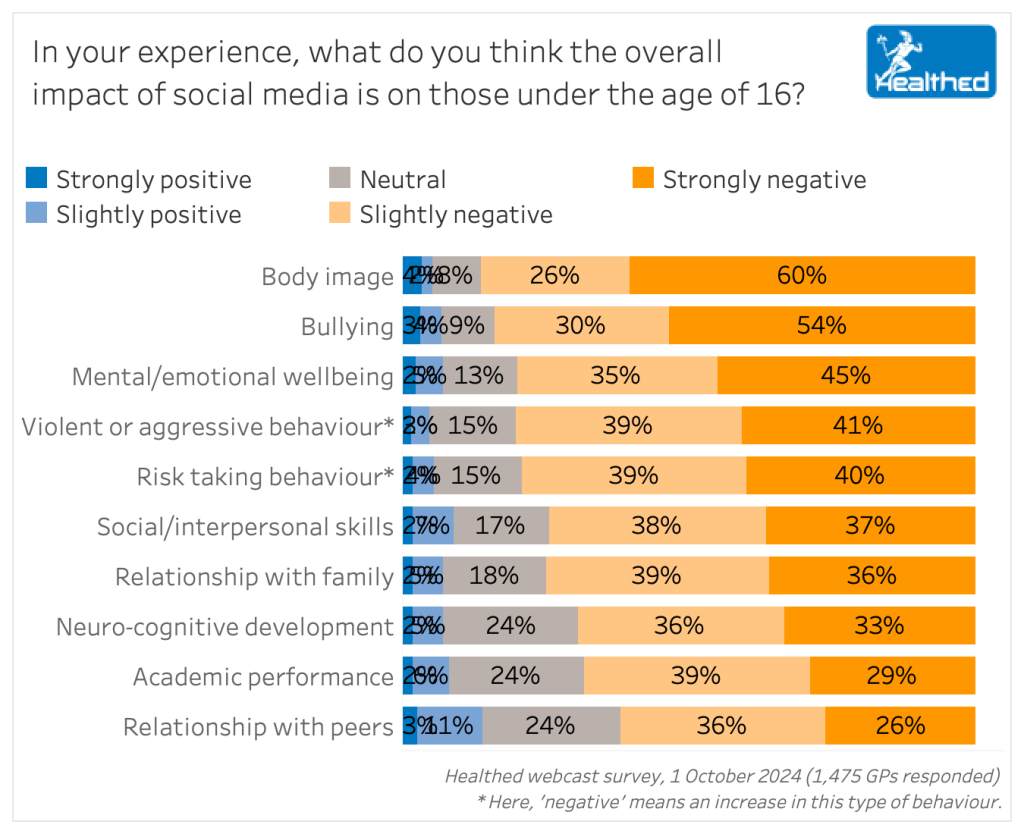

Most GPs say social media is negatively impacting children’s emotional and mental wellbeing, body image, neurocognitive development and social issues such as bullying, violent behaviour, and relationships.

In a survey last year GPs identified similar effects with smart-phone use.

Dr Rachael Sharman, Senior Lecturer in psychology at the University of the Sunshine Coast says there is mounting evidence that social media “is out of hand, and we have a range of downstream problems.”

For example a recent systematic review examining the link between social media and mental health in adolescents and young adults found that “smartphone and social media use among teenagers relates to an increase in mental distress, self-harming behaviours, and suicidality.”

Social media has a negative effect on body image, according to 86% of GPs – with 60% saying it has a strongly negative impact.

Dr Sharman agrees.

Young people, especially girls, have way more images to compare themselves with than they did in the past, when social circles consisted of about 100 to 200 people, Dr Sharman notes.

“Fast forward to now and you are comparing yourself not only to the 0.0001% of what the cultural ideal says you should look like, but also highly manipulated and photoshopped images as well.”

“These girls are being led up the garden path believing that this represents an attainable ideal, when in fact usually nothing could be further from the truth.”

Importantly, teenagers’ critical thinking skills are not fully developed, making it difficult for them to put idealised body images into perspective, Dr Sharman says.

Time spent on social media can leave less room for activities that promote healthy development, such as play and family time, Dr Sharman notes.

“It kind of tricks the brain into believing that you’re having a genuine social interaction when in fact you’re not. I think that’s where it gets quite nefarious. So people look at their friends and go, ‘oh, I’ve got 700 friends on Facebook or Instagram or whatever.”

But these people are often fair-weather friends who won’t be there when someone has a genuine problem, she says.

“You’re also not interacting with those people in real life and actually getting that back and forth, that engagement of mirror neurons, that engagement of emotions and the spoken word and body language and all that stuff that you actually need to learn.”

“You’re born with the rudimentary aspects of these skills. But you need to build upon those and learn those via experience––and real-life experience.”

Dr Sharman supports the ban—and hopes the age limit will be extended.

“I think it should be 18 in a perfect world. I’m really hoping this will go the same way as smoking. So we’ll start off with some level of restrictions, and if anything, hopefully they’ll actually escalate as time goes on.”

Some doctors agree: “Social media ban for all children until after high school should have been done long ago,” one survey respondent wrote. “Hopefully we can reverse the negative effects already seen in the community.”

But many GPs say a ban will be tricky to enforce, with many saying educating kids to use social media safely and responsibly would be more effective.

“Education about the harms of social media and reduced screen times seems better than a blanket ban,” one GP wrote.

“Whatever is proscribed by law will have technological loopholes or weaknesses which children will find a way to circumvent,” another said.

Digital behaviour expert Dr Joanne Orlando from Western Sydney University’s School of Education and Institute for Culture and Society favours an educational approach.

“Restricting children’s access to social media won’t stop them having to face the problem of online harms–it just puts the problem on hold,” Dr Orlando says.

That’s because children still face many of the same issues, such as bullying and body image concerns, at the age they can use social media, she explains.

“Rather than banning it, the best way to help young people navigate social media safely is to improve their social media literacy,” Dr Orlando says.

This involves “understanding and thinking critically about what you see on social media—and why,” she explains, suggesting schools could provide social media literacy classes for children and parents.

However, history has shown legislation is often needed to engender behavioural change, Dr Sharman says, citing cigarette smoking, drink-driving and seat belts as examples.

She says restrictions provide a platform for getting kids off social media, which often requires prolonged abstinence.

“This is where a ban comes in handy, because it’s a big ask for a doctor or a teacher or myself, a psychologist, anyone, to say to someone, get off social media for three months, stay off it, don’t go on it at all, have your family do the same,” she says.

“At the moment, it’s tricky to do that.”

Some GPs also noted this as a potential benefit of a ban.

“While this may seem draconian, government playing ‘bad cop’ allows parents to adopt the ‘good cop’ role in influencing their children re social media usage,” one respondent said.

“Immature minds are unable to manage the risks, pitfalls, and traps associated with unregulated social media.”

“Some social media needs to be restricted, but it can be a valuable form of connection for young people depending on their family and other social circumstances.”

“Kids get addicted to I-pads and I-phones and social media is very distracting and dangerous.”

“This is an area where parents need to take responsibility, but the government should provide education and support.”

“Will need to provide alternative though when they are banned. Maybe more sponsorships for outdoor sports activities.”

“The government should also provide free paediatric counselling and support, offer funding to encourage inclusive activities e.g. boot camps, sporting events, artistic exposes ie alternative activities that create acceptance of diversity to distract their minds positively and constructively.”

“Parents should be educated on how to manage their children’s behavior around social media.”

“It can be very useful for some who are socially isolated due to distance.”

“The family should have decision-making capacity, otherwise it feels like prohibition,” wrote one respondent.

Multiple Sclerosis vs Antibody Disease – What GPs Need to Know

Using SGLT2 to Reduce Cardiovascular Death in T2D – Important Updates for GPs

Menopause and MHT: Maximising Benefits & Minimising Risks

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Yes

No

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.

Menopause and MHT

Multiple sclerosis vs antibody disease

Using SGLT2 to reduce cardiovascular death in T2D

Peripheral arterial disease