Mark King has had the clap so many times he’s renamed it ‘the applause’. The first time King had gonorrhoea, he was a teenager in the late 1970s, growing up with his five siblings in Louisiana.

He had the telltale signs: burning and discomfort when he urinated and a thick discharge that left a stain in his underwear.

King visited a clinic and gave a fake name and phone number. He was treated quickly with antibiotics and sent on his way.

A few years later, the same symptoms reappeared. By this time, the 22-year-old was living in West Hollywood, hoping to launch his acting career.

While King had come out to his parents, being gay in Louisiana was poles apart from being gay in Los Angeles. For one, homosexuality was illegal in Louisiana until 2003, whereas California had legalised it in 1976.

In Los Angeles there was a thriving a gay scene where King, for the first time, could embrace his sexuality freely. He frequented bathhouses and also met men in dance clubs and along the bustling sidewalks. There was lots of sex to be had.

“The fact that we weren’t a fully formed culture beyond those spaces… was what brought us together as people. Sex was the only expression we had to claim ourselves as LGBT people,” King says.

When he stepped into the brick clinic just a few strides away from the heart of the city’s gay nightlife in Santa Monica, King, with his thick sandy blond hair with a tinge of red through it, looked around the room. It was filled with other gay men.

“What do you do when you’re 22 and gay? You cruise other men. I remember sitting in the lobby cruising other men,” King recalls, laughing. “My Summer of Love was 1982. It was a playground. I was young and on the prowl.”

Like a few years earlier, the doctor gave him a handful of antibiotics to take for a few days that would clear up the infection. It wasn’t a big deal. In fact, as King describes it, it was “simply an errand to run”.

“It was the price of doing business and it wasn’t a high price at all.”

But it was the calm before the storm, in more ways than one.

When King picked up gonorrhoea again in the 1990s, he was greatly relieved that treatment was now just one dose.

Penicillin was no longer effective, but ciprofloxacin was now the recommended treatment and it required only one dose. In King’s eyes, getting gonorrhoea was even less of a hassle.

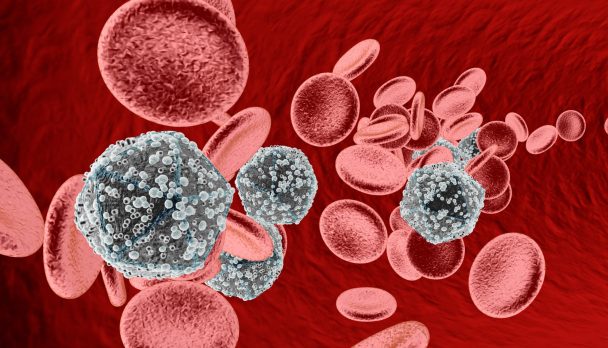

But this was actually a symptom of treatment regimens starting to fail. The bacteria Neisseria gonorrhoeae was on the way to developing resistance to nearly every drug ever used to treat it.

§

Newsletter:

On receiving the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for discovering penicillin, Alexander Fleming finished his lecture with a warning: “There is the danger,” he told the audience, “that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and, by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drug, make them resistant.”

In other words, we have known about bacteria’s ability to evolve resistance to drugs since the dawn of the antibiotic era.

Dr Manica Balasegaram is Director of the Global Antibiotic Research and Development Partnership (GARDP), based in Geneva. It’s a joint initiative between the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Initiative (DNDi) and the World Health Organization (WHO) and aims to develop new or improved treatments for bacterial infections.

“All antibiotics will have a shelf life – that’s just evolution,” he says. “It’s just a question of how quickly it will happen.”

Antibiotic resistance is one of the biggest threats to global health, food security and development. Common infections, such as pneumonia and tuberculosis, are becoming increasingly difficult to treat.

But GARDP has chosen to focus its attention on gonorrhoea as one of its four main priorities.

The sexually transmitted infection caught Balasegaram’s eyes for a host of reasons.

For one, a lot of the antibiotics that are currently used against gonorrhoea are used widely for other infections, and

N. gonorrhoeae has the ability to acquire resistance from other bacteria frighteningly quickly, meaning it can rapidly build up resistance.

Secondly, untreated gonorrhoea infections bring with them a range of potentially serious health implications that can have devastating consequences.

“Gonorrhoea is the most important sexually transmitted infection; it’s the one we’re most concerned about,” Balasegaram says.

Every year an estimated 78 million people are infected with gonorrhoea, making it the second most frequently reported sexually transmitted bacterial infection after chlamydia, according to WHO.

Gonorrhoea can infect the genitals, rectum and throat. Symptoms include discharge from the urethra or vagina and burning during urination called urethritis, caused by inflammation of the urethra. However, many who are infected don’t experience any symptoms, meaning they go undiagnosed and untreated.

Complications of untreated gonorrhoea can be severe and disproportionately affect women, who are more likely to experience no symptoms.

Untreated gonorrhoea not only increases the risk of contracting HIV but is also linked with an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease, which can cause ectopic pregnancy and infertility. A pregnant woman can also pass on the infection to her baby, which can cause blindness.

Fixing the threat of resistant gonorrhoea won’t be easy – the challenges in developing a new antibiotic can’t be overestimated.

Is the money for research and development (R&D) available? Who will the antibiotic be available to? And most importantly, how will you control its use so you can extend its shelf life?

What makes the search for a new antibiotic for gonorrhoea particularly challenging is the frequency of asymptomatic infections along with gonorrhoea’s ability to adapt to its host’s immune system and develop resistance to antibiotics.

A major concern is that because

N. gonorrhoeae can live in the throat without someone even knowing, the bug can acquire resistance from other bacteria that also live there and which have been exposed to antibiotics in the past. And with evidence that oral sex is becoming increasingly common in some parts of the world, this is particularly challenging.

“Oral sex is driving resistance. It’s a network of people having lots of oral sex. It’s the new norm,” says Dr Teodora Wi, a medical officer in WHO’s Department of Reproductive Health and Research in Geneva, talking specifically about Asia.

These challenges and concerns have gripped Balasegaram, but nonetheless he’s more determined than ever to bring a new drug to market.

“People are dying from drug-resistant infections. This is undoubtedly because this area has not been prioritised in the past because other areas of R&D are far more lucrative,” he says.

“Antibiotics are a global public good. I don’t think it’s easy to put a financial value to it.”

§

Recent data collected by WHO examined trends in drug-resistant gonorrhoea in 77 countries – countries that are part of the health agency’s Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP), a global network of regional and subregional laboratories that track the emergence and spread of resistance. And the results are grim.

More than 80 per cent of the countries that reported on azithromycin, a commonly prescribed antibiotic used to treat numerous common infections, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), found resistance.

Of greatest concern is that 66 per cent of countries surveyed have reported cases that resist last-resort antibiotics called extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs).

And as Wi points out, the real-world picture is undoubtedly far bleaker, because global surveillance for drug-resistant gonorrhoea is patchy and more frequently done in higher-income countries, which have greater resources. For example, of the 77 countries that were surveyed, few were in sub-Saharan Africa, a region where rates of gonorrhoea are high.

“We’re only seeing half of the real picture. We need to prepare for the future when there’s no cure,” Wi says.

But in a sign that time is running out, in March this year health experts’ worst fears were confirmed: a case of super-gonorrhoea, dubbed the world’s “worst ever” case, was found in a man who had attended a local sexual health clinic.

He had reportedly had sexual contact with a woman in South-east Asia.

Health officials said it was the first time this strain could not be cured with any of the antibiotics normally used to treat the disease. Although the patient has since responded to another antibiotic, doctors described him as “very lucky”. It’s an indication of a wider crisis – and one that knows no boundaries.

§

Thailand is one country on the front line of the fight against antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

It’s a key destination for the sex tourism industry, where STIs like gonorrhoea can spread easily and quickly across borders and beyond.

And like many other countries in the region, it has an over-the-counter culture of antibiotic access, which means patients put themselves at risk of being prescribed the wrong drugs – or even worse.

I’m in a district close to Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, to meet Boontham, a pharmacist. We meet in the jam-packed stockroom of the herbal medicine company he also runs – a business that’s far more lucrative than his pharmacy. The stockroom is filled head to toe with boxes of tablets containing an array of funky herbs I’ve never heard of.

The cost of visiting a doctor and the stigma surrounding STIs mean that many Thais rely on pharmacists like Boontham to cure their gonorrhoea.

But he might be doing more harm than good.

While Boontham has a degree in pharmacology and has been a pharmacist for more than 30 years, he has no idea of Thailand’s treatment guidelines for gonorrhoea. In fact, he’s more than a decade out of date.

And he can’t, of course, diagnose patients accurately, particularly because gonorrhoea has similar symptoms to chlamydia.

“If you’ve been doing this for a long time, you just do what you have to, and that’s an educated guess.”

“As of now I use ciprofloxacin [to treat gonorrhoea],” he says.

“If that doesn’t work, then I guess it’s chlamydia.”

I tell him, however, that gonorrhoea in Thailand, as in many other countries, has shown widespread resistance to ciprofloxacin – and that his country actually stopped recommending it more than a decade ago.

“It’s not resistant, even doctors use it,” he says.

“I prescribe it because it’s cheap. In hospitals they prescribe newer antibiotics that are more effective, but they’re more expensive.”

In countries where antibiotics are sold over the counter, research shows people are far more likely to visit pharmacists than a doctor.

But while experts acknowledge that restricting the sale of antibiotics – particularly in rural and remote areas where there are few, if any, proper doctors – isn’t the answer, this still presents a major challenge in the fight against drug-resistant infections.

“The problem is that when you go to a pharmacist and take antibiotics, maybe… your symptoms have disappeared, but in fact you still have the infection. That means you can transmit the infection and cause more resistance,” Wi says.

I ask Boontham whether he’s concerned about resistance – if he’s worried that the people he’s treated for gonorrhoea aren’t cured.

“Resistance to medication is a doctor’s job, not a pharmacist’s,” he says.

The casual handing out of antibiotics without a prescription is not only confined to Thailand. It’s a huge concern across the rest of the region and in other parts of the world, with no clear vision of how to tackle this growing problem.

Handing out antibiotics that likely no longer work for people with gonorrhoea has also been happening in high-income countries – countries that might be expected to have stricter treatment guidelines.

In fact, a study published in the

BMJ in 2015 found that many GPs in England were prescribing ciprofloxacin, even though it hasn’t been recommended for treating gonorrhoea since 2005. In 2007, ciprofloxacin still made up almost half of prescriptions for gonorrhoea. As recently as 2011, GPs still prescribed it in 20 per cent of cases.

§

On a balmy afternoon in bustling Bangkok, I visit Silom Community Clinic @ TropMed, an STI clinic north-east of the city centre dedicated to men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women who have sex with men.

Located on the 12th floor of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, the clinic is spotlessly clean, with bright purple walls, rainbow flags and a sign that immediately catches my eye, which reads “Suck, F*ck, Test, Repeat”.

Off the main corridor is a microbiology lab that is doing critical and urgent work in the fight against antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

In fact, the lab may be the best way Thailand can protect itself from this growing threat.

Dr Eileen Dunne is an American epidemiologist and the head of the behavioural and clinical research section of the HIV/STI programme here, which is run as part of a collaboration between Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). She, along with her Thai staff, are Thailand’s best line of defence in slowing gonorrhoea resistance.

In 2015, recognising the worldwide danger of increasingly difficult to treat gonorrhoea infections – and the specific threat they posed to Thailand – the US CDC, WHO and Thai MOPH joined forces to launch a programme to track and ultimately limit the spread of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

The programme is an enhanced local version of the WHO’s GASP and is the first of its kind in the world. It’s called EGASP.

It works like this. If a male patient comes into one of its two clinics with the telltale symptoms of gonorrhoea, he will have a sample collected for analysis and will fill out a questionnaire, which contains questions such as: “Did you take antibiotics in the last two weeks?” To create an open environment, the clinics are anonymous and the questionnaire is done privately on a computer.

Men are the target group in the programme, Dunne explains, because the yield for isolating

N. gonorrhoeae is very high among men who have urethritis compared with women and those who are asymptomatic. MSM are an important population, she adds, because research shows they are likelier to develop resistance earlier than the general population, for reasons that aren’t precisely known.

She and the laboratory staff take me to see if there are any samples being cultured from swabs taken from patients’ penises. Inside the incubator, where the samples are kept in Petri dishes at 36 degrees Celsius with 5 per cent carbon dioxide to promote bacteria growth, there are three.

The stench of agar, a brown gelatinous medium that provides nutrients and a stable environment for bacteria to grow, is overwhelming. One Petri dish contains a cluster of bubbly white dots, signalling that the patient does indeed have gonorrhoea.

The next step is antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) at a lab downstairs. The isolate will be measured for resistance to five antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin and the last-resort drugs cefixime and ceftriaxone. It’s resistance to these latter two which is of greatest concern.

From the beginning of EGASP until 20 October 2017, of the 845 confirmed diagnoses of gonorrhoea that underwent AST, almost all isolates had widespread resistance to ciprofloxacin, as in many other countries.

But encouragingly, none have shown resistance to the last-line drugs.

That’s a relief for Thailand, but in no way an indication that Dunne and her team’s alacrity should wane.

“People are surprised and have asked, ‘Oh, why are you doing this if you don’t show resistance?’,” Dunne says.

“It’s actually good to do surveillance and not be detecting resistance yet. It means that we’re early enough to be prepared… and [to] have a plan of response.

“Having strong surveillance activity in a region in which this is likely to emerge is important so we can detect it early.”

Thailand’s neighbours, specifically Myanmar, India, Indonesia and China, have recorded a significantly higher percentage of gonorrhoea isolates that are resistant to last-line treatments compared to Thailand.

With the increasing movement of people around the world and Thailand’s popularity for sex tourism, I can see just how rapidly this threat could have far-reaching consequences.

“I think it’s really important to detect early, even one case, [because] it can be a harbinger for future developments of resistance. These bacteria are transmitted very rapidly between people. Being able to really find that one case early means that special steps can be in place to control transmission,” Dunne says.

I ask if the focus on MSM means other groups might be being missed. What about women, who are more likely than men to not experience any gonorrhoea symptoms?

Or itinerant sex workers from across the border in Myanmar and Cambodia? I wonder if, among this high-risk group, EGASP is missing some of Thailand’s most vulnerable. I ask if there’s potential for the programme to extend its work to include these people and their partners.

Dunne agrees it’s a good idea. “This targeted approach in men with symptoms is purposeful but may not be generalisable to the whole population. It’s the tip of the iceberg.”

But it’s early on in the programme, and she and the team have to start somewhere.

“We need more time,” she says.

But no one is really sure how much time Thailand – and the rest of the world – has.

§

The number of people infected with gonorrhoea has risen rapidly in recent years. Australia has seen a 63 per cent increase in the number of reported gonorrhoea cases since 2012, with the fastest rate of increase being in young heterosexual urbanites. In England, gonorrhoea cases rose by 53 per cent between 2012 and 2015, led by young people, gay men and other MSM. Meanwhile, in the USA cases rose by nearly 50 per cent between 2009 and 2016.

And according to some experts, one of science’s greatest achievements in the fight against HIV could be a factor.

Like many, Mark King’s nonchalant attitude towards sex had come to a halt when the HIV epidemic hit the gay community in the USA. No longer was gonorrhoea simply seen as a small, insignificant price to pay for a night of fun.

“Half the fun of being gay [was that] you didn’t have to worry about birth control. Condoms were birth control, not STI control,” says King.

“[But] as the years passed and you get into the 90s and we know how HIV is transmitted, to get gonorrhoea is shameful because it means that you’ve been taking risks that could transmit HIV.

“Suddenly gonorrhoea became this really shameful thing because it means you’re not doing the right thing.”

Move forward to today and HIV is no longer the death threat it once was.

A strong civil society movement saw the disease get the political – and scientific – attention it warranted. The development of life-saving drugs means that those with HIV can live long, healthy lives.

But as HIV treatment and prevention methods improve, people’s perception of risk may be changing.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a daily pill for people who don’t have HIV but who are at substantial risk of getting it. It’s a powerful tool in the fight against HIV, it is argued. When taken every day, it’s up to 92 per cent effective in preventing infection.

But with its development and uptake came alarm bells, with some warning that STI rates would increase among those who used PrEP. Some small studies have hinted that this may be happening.

Not all experts agree with this. The data from these studies is ambiguous and cannot be generalised. And some say that regular testing regimes associated with PrEP prescriptions could prevent STIs spreading.

However, just as with antibiotics, there are people using PrEP without getting it through official health outlets. A recent survey carried out across Europe by the HIV/AIDS advocacy group AIDES found that about 70 per cent of informal PrEP users were having no regular medical monitoring.

King is one of many for whom concerns over STIs in the broader context of having the incredible ability to prevent HIV infection seems absurd.

“PrEP opens the door for people to have sex without fear of HIV infection. The reaction is: yes, but what do we do about STIs? Oh my god, gonorrhoea and syphilis,” King says sarcastically.

“People ask me, how does a person get HIV or gonorrhoea in this day and age? Well, let’s see: because they were horny, or they said yes when they should have said no, or they had too much to drink, or they fell in love, or they trusted the wrong person.”

King’s words may resonate with many around the world. But WHO is focused on increasing condom use. Wi is particularly worried about the proliferation and popularity of dating apps among young people, which she believes are making no-strings-attached sex easier to obtain.

“All of us need to be strong about condom use. All of us need to campaign for condom use,” Wi says.

§

Looking ahead, at what point will it be more common to have a gonorrhoea infection that can’t be treated with antibiotics than one that can? The answer is difficult to predict, but it’s also a potential reality that isn’t far-fetched.

“We are in a situation now where we are worryingly using the last line of antibiotics for many infections or seeing even resistance to these last-line antibiotics,” Balasegaram says.

But as GARDP works to bring a new antibiotic to market, some countries are getting desperate as resistance to the available treatments continues to spread.

Australia, which has recorded widespread resistance to azithromycin, is considering going back to an old drug called spectinomycin.

Spectinomycin involves a painful muscular injection and has been linked to toxicity and a range of side-effects. Another concern is that it’s in short supply because it’s rarely used around the world any more.

To this end, R&D for new antibiotics is urgent.

But antibiotic drug development is prohibitively expensive and not attractive to the pharmaceutical industry – even more so when it’s for an STI.

In response, GARDP has partnered with Entasis Therapeutics, a US biotech company, to accelerate the development of a new antibiotic that will be produced specifically to target drug-resistant gonorrhoea.

Zoliflodacin is a novel first-in-class oral antibiotic – in other words, a new and unique mechanism of potentially treating gonorrhoea – and is one of only three potential new antibiotic candidates currently undergoing trials. It had previously been put through clinical trials in 2015, but a lack of investment stopped the drug from progressing further.

This year GARDP and Entasis will launch the last phase of trials of zoliflodacin, involving 650 people in Thailand, South Africa, the USA and parts of Europe.

If the drug is approved by regulators, Entasis will permit GARDP to introduce it in 168 low- and middle-income countries. It’s hoping it will be registered by 2021 and available on the market by 2023.

A major strength of the partnership between GARDP and Entasis is that it will be able to limit what infections zoliflodacin is used for.

“We’re trying to focus this drug specifically on STIs – not other community infections where antibiotics are widely used,” Balasegaram says.

“The aim is not to go beyond that because that’s how resistance starts.”

To this end, initially the drug will be licensed only for use against gonorrhoea infections. If it proves to be effective against chlamydia and

Mycoplasma genitalium (another bacterial STI), the GARDP and Entasis partnership could license it for those two infections as well, subject to clinical trials.

“We will support clinical trials and registration and therefore we can play a big role in how it is responsibly introduced and used. That gives us more control in how the drug is introduced and marketed in the countries where we work,” says Balasegaram.

Dunne is excited that Thailand will be part of the trials.

“It is the underbelly of infections. It doesn’t get the attention it deserves and that is why this is exciting,” she says.

A lot is riding on the success of the drug. Will zoliflodacin be successful in remaining effective for as long as possible? Or will it face the same fate as other antibiotics?

Moreover, research is risky – there’s no guarantee the clinical trials will be successful.

“We still don’t know whether this project will succeed or not,” says Balasegaram. “But it’s a project that we feel is extremely important and that we’re very committed to.”

The development of new antibiotics raises myriad questions: How can we ensure they are used appropriately so we can preserve their effectiveness? And how can we ensure those who really need the drugs get them?

One way would be a point-of-care rapid diagnostic test – ideally one that could predict which antibiotics will work on a particular infection and that could be used in settings around the world.

Balasegaram says they’ve been looking for a simple diagnostic tool like this but haven’t yet found one. Diagnostic tools aside, the responsible use of new antibiotics also relies on robust national and international treatment guidelines and strong regulatory authorities to guide and monitor antibiotic use.

“If you have developed an antibiotic for narrow use, you have to think about how to market the drug. We do not want to drop large quantities of it around the world. But we also want to make sure those who need it get it,” he says.

This is where strong surveillance programmes, like Thailand’s, are critical.

But it’s inevitable that bugs will develop resistance to the next antibiotic and then the next. So Balasegaram wants more investment in R&D that focuses not only on new antibiotics but also on alternative ways to treat bacterial infections.

“We have to continue to do R&D into… therapeutic ways to treat these infections differently,” he says.

“This may include novel and non-conventional approaches. I think that is a job that is going to last decades.”

What that might look like is complex.

It may include designing antibodies that specifically target bacteria or using bacteriophages – viruses that infect bacteria – as a replacement for antibiotics.

Either way, many feel that the end of the antibiotic era is near and that the transition from antibiotics to non-traditional treatments poses major challenges that won’t be easy to solve.

“It’s worth bearing in mind that bacteria can evolve to different approaches we develop,” says Balasegaram.

“I don’t think we will see a magic bullet solution soon that will definitively solve the issue.”

It’s a frightening thought.

Mark King has had the clap so many times he’s renamed it ‘the applause’. The first time King had gonorrhoea, he was a teenager in the late 1970s, growing up with his five siblings in Louisiana.

He had the telltale signs: burning and discomfort when he urinated and a thick discharge that left a stain in his underwear.

King visited a clinic and gave a fake name and phone number. He was treated quickly with antibiotics and sent on his way.

A few years later, the same symptoms reappeared. By this time, the 22-year-old was living in West Hollywood, hoping to launch his acting career.

While King had come out to his parents, being gay in Louisiana was poles apart from being gay in Los Angeles. For one, homosexuality was illegal in Louisiana until 2003, whereas California had legalised it in 1976.

In Los Angeles there was a thriving a gay scene where King, for the first time, could embrace his sexuality freely. He frequented bathhouses and also met men in dance clubs and along the bustling sidewalks. There was lots of sex to be had.

“The fact that we weren’t a fully formed culture beyond those spaces… was what brought us together as people. Sex was the only expression we had to claim ourselves as LGBT people,” King says.

When he stepped into the brick clinic just a few strides away from the heart of the city’s gay nightlife in Santa Monica, King, with his thick sandy blond hair with a tinge of red through it, looked around the room. It was filled with other gay men.

“What do you do when you’re 22 and gay? You cruise other men. I remember sitting in the lobby cruising other men,” King recalls, laughing. “My Summer of Love was 1982. It was a playground. I was young and on the prowl.”

Like a few years earlier, the doctor gave him a handful of antibiotics to take for a few days that would clear up the infection. It wasn’t a big deal. In fact, as King describes it, it was “simply an errand to run”.

“It was the price of doing business and it wasn’t a high price at all.”

But it was the calm before the storm, in more ways than one.

When King picked up gonorrhoea again in the 1990s, he was greatly relieved that treatment was now just one dose.

Penicillin was no longer effective, but ciprofloxacin was now the recommended treatment and it required only one dose. In King’s eyes, getting gonorrhoea was even less of a hassle.

But this was actually a symptom of treatment regimens starting to fail. The bacteria

Neisseria gonorrhoeae was on the way to developing resistance to nearly every drug ever used to treat it.

§

Recent data collected by WHO examined trends in drug-resistant gonorrhoea in 77 countries – countries that are part of the health agency’s Gonococcal Antimicrobial Surveillance Programme (GASP), a global network of regional and subregional laboratories that track the emergence and spread of resistance. And the results are grim.

More than 80 per cent of the countries that reported on azithromycin, a commonly prescribed antibiotic used to treat numerous common infections, including sexually transmitted infections (STIs), found resistance.

Of greatest concern is that 66 per cent of countries surveyed have reported cases that resist last-resort antibiotics called extended-spectrum cephalosporins (ESCs).

And as Wi points out, the real-world picture is undoubtedly far bleaker, because global surveillance for drug-resistant gonorrhoea is patchy and more frequently done in higher-income countries, which have greater resources. For example, of the 77 countries that were surveyed, few were in sub-Saharan Africa, a region where rates of gonorrhoea are high.

“We’re only seeing half of the real picture. We need to prepare for the future when there’s no cure,” Wi says.

But in a sign that time is running out, in March this year health experts’ worst fears were confirmed: a case of super-gonorrhoea, dubbed the world’s “worst ever” case, was found in a man who had attended a local sexual health clinic.

He had reportedly had sexual contact with a woman in South-east Asia.

Health officials said it was the first time this strain could not be cured with any of the antibiotics normally used to treat the disease. Although the patient has since responded to another antibiotic, doctors described him as “very lucky”. It’s an indication of a wider crisis – and one that knows no boundaries.

§

Thailand is one country on the front line of the fight against antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

It’s a key destination for the sex tourism industry, where STIs like gonorrhoea can spread easily and quickly across borders and beyond.

And like many other countries in the region, it has an over-the-counter culture of antibiotic access, which means patients put themselves at risk of being prescribed the wrong drugs – or even worse.

I’m in a district close to Thailand’s capital, Bangkok, to meet Boontham, a pharmacist. We meet in the jam-packed stockroom of the herbal medicine company he also runs – a business that’s far more lucrative than his pharmacy. The stockroom is filled head to toe with boxes of tablets containing an array of funky herbs I’ve never heard of.

The cost of visiting a doctor and the stigma surrounding STIs mean that many Thais rely on pharmacists like Boontham to cure their gonorrhoea.

But he might be doing more harm than good.

While Boontham has a degree in pharmacology and has been a pharmacist for more than 30 years, he has no idea of Thailand’s treatment guidelines for gonorrhoea. In fact, he’s more than a decade out of date.

And he can’t, of course, diagnose patients accurately, particularly because gonorrhoea has similar symptoms to chlamydia.

“If you’ve been doing this for a long time, you just do what you have to, and that’s an educated guess.”

“As of now I use ciprofloxacin [to treat gonorrhoea],” he says.

“If that doesn’t work, then I guess it’s chlamydia.”

I tell him, however, that gonorrhoea in Thailand, as in many other countries, has shown widespread resistance to ciprofloxacin – and that his country actually stopped recommending it more than a decade ago.

“It’s not resistant, even doctors use it,” he says.

“I prescribe it because it’s cheap. In hospitals they prescribe newer antibiotics that are more effective, but they’re more expensive.”

In countries where antibiotics are sold over the counter, research shows people are far more likely to visit pharmacists than a doctor.

But while experts acknowledge that restricting the sale of antibiotics – particularly in rural and remote areas where there are few, if any, proper doctors – isn’t the answer, this still presents a major challenge in the fight against drug-resistant infections.

“The problem is that when you go to a pharmacist and take antibiotics, maybe… your symptoms have disappeared, but in fact you still have the infection. That means you can transmit the infection and cause more resistance,” Wi says.

I ask Boontham whether he’s concerned about resistance – if he’s worried that the people he’s treated for gonorrhoea aren’t cured.

“Resistance to medication is a doctor’s job, not a pharmacist’s,” he says.

The casual handing out of antibiotics without a prescription is not only confined to Thailand. It’s a huge concern across the rest of the region and in other parts of the world, with no clear vision of how to tackle this growing problem.

Handing out antibiotics that likely no longer work for people with gonorrhoea has also been happening in high-income countries – countries that might be expected to have stricter treatment guidelines.

In fact, a study published in the

BMJ in 2015 found that many GPs in England were prescribing ciprofloxacin, even though it hasn’t been recommended for treating gonorrhoea since 2005. In 2007, ciprofloxacin still made up almost half of prescriptions for gonorrhoea. As recently as 2011, GPs still prescribed it in 20 per cent of cases.

§

On a balmy afternoon in bustling Bangkok, I visit Silom Community Clinic @ TropMed, an STI clinic north-east of the city centre dedicated to men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender women who have sex with men.

Located on the 12th floor of the Hospital for Tropical Diseases, the clinic is spotlessly clean, with bright purple walls, rainbow flags and a sign that immediately catches my eye, which reads “Suck, F*ck, Test, Repeat”.

Off the main corridor is a microbiology lab that is doing critical and urgent work in the fight against antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

In fact, the lab may be the best way Thailand can protect itself from this growing threat.

Dr Eileen Dunne is an American epidemiologist and the head of the behavioural and clinical research section of the HIV/STI programme here, which is run as part of a collaboration between Thailand’s Ministry of Public Health (MOPH) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). She, along with her Thai staff, are Thailand’s best line of defence in slowing gonorrhoea resistance.

In 2015, recognising the worldwide danger of increasingly difficult to treat gonorrhoea infections – and the specific threat they posed to Thailand – the US CDC, WHO and Thai MOPH joined forces to launch a programme to track and ultimately limit the spread of antibiotic-resistant gonorrhoea.

The programme is an enhanced local version of the WHO’s GASP and is the first of its kind in the world. It’s called EGASP.

It works like this. If a male patient comes into one of its two clinics with the telltale symptoms of gonorrhoea, he will have a sample collected for analysis and will fill out a questionnaire, which contains questions such as: “Did you take antibiotics in the last two weeks?” To create an open environment, the clinics are anonymous and the questionnaire is done privately on a computer.

Men are the target group in the programme, Dunne explains, because the yield for isolating

N. gonorrhoeae is very high among men who have urethritis compared with women and those who are asymptomatic. MSM are an important population, she adds, because research shows they are likelier to develop resistance earlier than the general population, for reasons that aren’t precisely known.

She and the laboratory staff take me to see if there are any samples being cultured from swabs taken from patients’ penises. Inside the incubator, where the samples are kept in Petri dishes at 36 degrees Celsius with 5 per cent carbon dioxide to promote bacteria growth, there are three.

The stench of agar, a brown gelatinous medium that provides nutrients and a stable environment for bacteria to grow, is overwhelming. One Petri dish contains a cluster of bubbly white dots, signalling that the patient does indeed have gonorrhoea.

The next step is antibiotic susceptibility testing (AST) at a lab downstairs. The isolate will be measured for resistance to five antibiotics, including ciprofloxacin and the last-resort drugs cefixime and ceftriaxone. It’s resistance to these latter two which is of greatest concern.

From the beginning of EGASP until 20 October 2017, of the 845 confirmed diagnoses of gonorrhoea that underwent AST, almost all isolates had widespread resistance to ciprofloxacin, as in many other countries.

But encouragingly, none have shown resistance to the last-line drugs.

That’s a relief for Thailand, but in no way an indication that Dunne and her team’s alacrity should wane.

“People are surprised and have asked, ‘Oh, why are you doing this if you don’t show resistance?’,” Dunne says.

“It’s actually good to do surveillance and not be detecting resistance yet. It means that we’re early enough to be prepared… and [to] have a plan of response.

“Having strong surveillance activity in a region in which this is likely to emerge is important so we can detect it early.”

Thailand’s neighbours, specifically Myanmar, India, Indonesia and China, have recorded a significantly higher percentage of gonorrhoea isolates that are resistant to last-line treatments compared to Thailand.

With the increasing movement of people around the world and Thailand’s popularity for sex tourism, I can see just how rapidly this threat could have far-reaching consequences.

“I think it’s really important to detect early, even one case, [because] it can be a harbinger for future developments of resistance. These bacteria are transmitted very rapidly between people. Being able to really find that one case early means that special steps can be in place to control transmission,” Dunne says.

I ask if the focus on MSM means other groups might be being missed. What about women, who are more likely than men to not experience any gonorrhoea symptoms?

Or itinerant sex workers from across the border in Myanmar and Cambodia? I wonder if, among this high-risk group, EGASP is missing some of Thailand’s most vulnerable. I ask if there’s potential for the programme to extend its work to include these people and their partners.

Dunne agrees it’s a good idea. “This targeted approach in men with symptoms is purposeful but may not be generalisable to the whole population. It’s the tip of the iceberg.”

But it’s early on in the programme, and she and the team have to start somewhere.

“We need more time,” she says.

But no one is really sure how much time Thailand – and the rest of the world – has.

§

The number of people infected with gonorrhoea has risen rapidly in recent years. Australia has seen a 63 per cent increase in the number of reported gonorrhoea cases since 2012, with the fastest rate of increase being in young heterosexual urbanites. In England, gonorrhoea cases rose by 53 per cent between 2012 and 2015, led by young people, gay men and other MSM. Meanwhile, in the USA cases rose by nearly 50 per cent between 2009 and 2016.

And according to some experts, one of science’s greatest achievements in the fight against HIV could be a factor.

Like many, Mark King’s nonchalant attitude towards sex had come to a halt when the HIV epidemic hit the gay community in the USA. No longer was gonorrhoea simply seen as a small, insignificant price to pay for a night of fun.

“Half the fun of being gay [was that] you didn’t have to worry about birth control. Condoms were birth control, not STI control,” says King.

“[But] as the years passed and you get into the 90s and we know how HIV is transmitted, to get gonorrhoea is shameful because it means that you’ve been taking risks that could transmit HIV.

“Suddenly gonorrhoea became this really shameful thing because it means you’re not doing the right thing.”

Move forward to today and HIV is no longer the death threat it once was.

A strong civil society movement saw the disease get the political – and scientific – attention it warranted. The development of life-saving drugs means that those with HIV can live long, healthy lives.

But as HIV treatment and prevention methods improve, people’s perception of risk may be changing.

Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is a daily pill for people who don’t have HIV but who are at substantial risk of getting it. It’s a powerful tool in the fight against HIV, it is argued. When taken every day, it’s up to 92 per cent effective in preventing infection.

But with its development and uptake came alarm bells, with some warning that STI rates would increase among those who used PrEP. Some small studies have hinted that this may be happening.

Not all experts agree with this. The data from these studies is ambiguous and cannot be generalised. And some say that regular testing regimes associated with PrEP prescriptions could prevent STIs spreading.

However, just as with antibiotics, there are people using PrEP without getting it through official health outlets. A recent survey carried out across Europe by the HIV/AIDS advocacy group AIDES found that about 70 per cent of informal PrEP users were having no regular medical monitoring.

King is one of many for whom concerns over STIs in the broader context of having the incredible ability to prevent HIV infection seems absurd.

“PrEP opens the door for people to have sex without fear of HIV infection. The reaction is: yes, but what do we do about STIs? Oh my god, gonorrhoea and syphilis,” King says sarcastically.

“People ask me, how does a person get HIV or gonorrhoea in this day and age? Well, let’s see: because they were horny, or they said yes when they should have said no, or they had too much to drink, or they fell in love, or they trusted the wrong person.”

King’s words may resonate with many around the world. But WHO is focused on increasing condom use. Wi is particularly worried about the proliferation and popularity of dating apps among young people, which she believes are making no-strings-attached sex easier to obtain.

“All of us need to be strong about condom use. All of us need to campaign for condom use,” Wi says.

§

Looking ahead, at what point will it be more common to have a gonorrhoea infection that can’t be treated with antibiotics than one that can? The answer is difficult to predict, but it’s also a potential reality that isn’t far-fetched.

“We are in a situation now where we are worryingly using the last line of antibiotics for many infections or seeing even resistance to these last-line antibiotics,” Balasegaram says.

But as GARDP works to bring a new antibiotic to market, some countries are getting desperate as resistance to the available treatments continues to spread.

Australia, which has recorded widespread resistance to azithromycin, is considering going back to an old drug called spectinomycin.

Spectinomycin involves a painful muscular injection and has been linked to toxicity and a range of side-effects. Another concern is that it’s in short supply because it’s rarely used around the world any more.

To this end, R&D for new antibiotics is urgent.

But antibiotic drug development is prohibitively expensive and not attractive to the pharmaceutical industry – even more so when it’s for an STI.

In response, GARDP has partnered with Entasis Therapeutics, a US biotech company, to accelerate the development of a new antibiotic that will be produced specifically to target drug-resistant gonorrhoea.

Zoliflodacin is a novel first-in-class oral antibiotic – in other words, a new and unique mechanism of potentially treating gonorrhoea – and is one of only three potential new antibiotic candidates currently undergoing trials. It had previously been put through clinical trials in 2015, but a lack of investment stopped the drug from progressing further.

This year GARDP and Entasis will launch the last phase of trials of zoliflodacin, involving 650 people in Thailand, South Africa, the USA and parts of Europe.

If the drug is approved by regulators, Entasis will permit GARDP to introduce it in 168 low- and middle-income countries. It’s hoping it will be registered by 2021 and available on the market by 2023.

A major strength of the partnership between GARDP and Entasis is that it will be able to limit what infections zoliflodacin is used for.

“We’re trying to focus this drug specifically on STIs – not other community infections where antibiotics are widely used,” Balasegaram says.

“The aim is not to go beyond that because that’s how resistance starts.”

To this end, initially the drug will be licensed only for use against gonorrhoea infections. If it proves to be effective against chlamydia and

Mycoplasma genitalium (another bacterial STI), the GARDP and Entasis partnership could license it for those two infections as well, subject to clinical trials.

“We will support clinical trials and registration and therefore we can play a big role in how it is responsibly introduced and used. That gives us more control in how the drug is introduced and marketed in the countries where we work,” says Balasegaram.

Dunne is excited that Thailand will be part of the trials.

“It is the underbelly of infections. It doesn’t get the attention it deserves and that is why this is exciting,” she says.

A lot is riding on the success of the drug. Will zoliflodacin be successful in remaining effective for as long as possible? Or will it face the same fate as other antibiotics?

Moreover, research is risky – there’s no guarantee the clinical trials will be successful.

“We still don’t know whether this project will succeed or not,” says Balasegaram. “But it’s a project that we feel is extremely important and that we’re very committed to.”

The development of new antibiotics raises myriad questions: How can we ensure they are used appropriately so we can preserve their effectiveness? And how can we ensure those who really need the drugs get them?

One way would be a point-of-care rapid diagnostic test – ideally one that could predict which antibiotics will work on a particular infection and that could be used in settings around the world.

Balasegaram says they’ve been looking for a simple diagnostic tool like this but haven’t yet found one. Diagnostic tools aside, the responsible use of new antibiotics also relies on robust national and international treatment guidelines and strong regulatory authorities to guide and monitor antibiotic use.

“If you have developed an antibiotic for narrow use, you have to think about how to market the drug. We do not want to drop large quantities of it around the world. But we also want to make sure those who need it get it,” he says.

This is where strong surveillance programmes, like Thailand’s, are critical.

But it’s inevitable that bugs will develop resistance to the next antibiotic and then the next. So Balasegaram wants more investment in R&D that focuses not only on new antibiotics but also on alternative ways to treat bacterial infections.

“We have to continue to do R&D into… therapeutic ways to treat these infections differently,” he says.

“This may include novel and non-conventional approaches. I think that is a job that is going to last decades.”

What that might look like is complex.

It may include designing antibodies that specifically target bacteria or using bacteriophages – viruses that infect bacteria – as a replacement for antibiotics.

Either way, many feel that the end of the antibiotic era is near and that the transition from antibiotics to non-traditional treatments poses major challenges that won’t be easy to solve.

“It’s worth bearing in mind that bacteria can evolve to different approaches we develop,” says Balasegaram.

“I don’t think we will see a magic bullet solution soon that will definitively solve the issue.”

It’s a frightening thought.

This

article first appeared on

Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence.