Articles / Frontrunners for Australia’s COVID-19 vaccine

0 hours

These are activities that expand general practice knowledge, skills and attitudes, related to your scope of practice.

0 hours

These are activities that require reflection on feedback about your work.

0 hours

These are activities that use your work data to ensure quality results.

These are activities that expand general practice knowledge, skills and attitudes, related to your scope of practice.

These are activities that require reflection on feedback about your work.

These are activities that use your work data to ensure quality results.

On Sunday, the Australian government announced it would put A$6 million towards the research and development of three local COVID-19 vaccine candidates, via the Medical Research Future Fund.

The three candidates to share this funding are:

Let’s take a look at these different approaches.

I’m part of the Monash team working with scientists at the Doherty Institute on both the protein vaccine and the mRNA vaccine. Although we initially developed these vaccine candidates separately, they target a similar part of the virus — so we’ve now joined forces to further develop the two together.

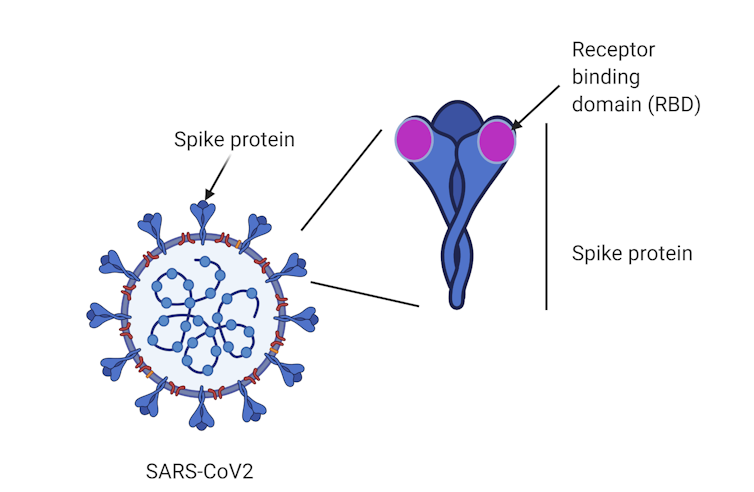

Until now, vaccine candidates, such as those developed by the University of Queensland and the University of Oxford, have generally used the entire spike protein as a target. The spike is a large protein found on the surface of SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

A region at the tip of the spike called the “receptor-binding domain” enables the virus to establish itself by binding to our cells and causing infection.

Instead of vaccinating against the “whole” spike protein, our approach is unique in that it uses the receptor-binding domain tip.

The subunit protein vaccine contains the receptor-binding domain from SARS-CoV-2 as the antigen, or target. Exposing our immune system to this protein is intended to create antibodies that generate immunity against this part of the virus, protecting us if we encounter SARS-CoV-2 in the future.

For the mRNA vaccine, rather than injecting the protein itself, a short piece of the genetic material from the virus (mRNA) provides a blueprint to make the receptor-binding domain. So this vaccine also targets the receptor-binding domain to induce an immune response, although the process is different.

We’re exploring the two vaccine options simultaneously. One may prevail as the most promising candidate. It’s also possible one candidate might be the primary vaccine and the other could serve as a booster — it’s still early to tell.

The funding we’ve received will support the development and manufacturing of the two candidates with the intention to enter phase 1 human trials next year if the vaccines prove promising in mice and monkeys. Early results are encouraging.

Notably, both of these vaccines can be produced and manufactured rapidly. For example, within three weeks of receiving the genetic sequence of SARS-CoV-2, we were able to produce three mRNA vaccine candidates.

This flexibility of the Doherty/MIPS approach will be particularly important if COVID-19 mutates into a new strain, and could also be useful for vaccine development in future pandemics.

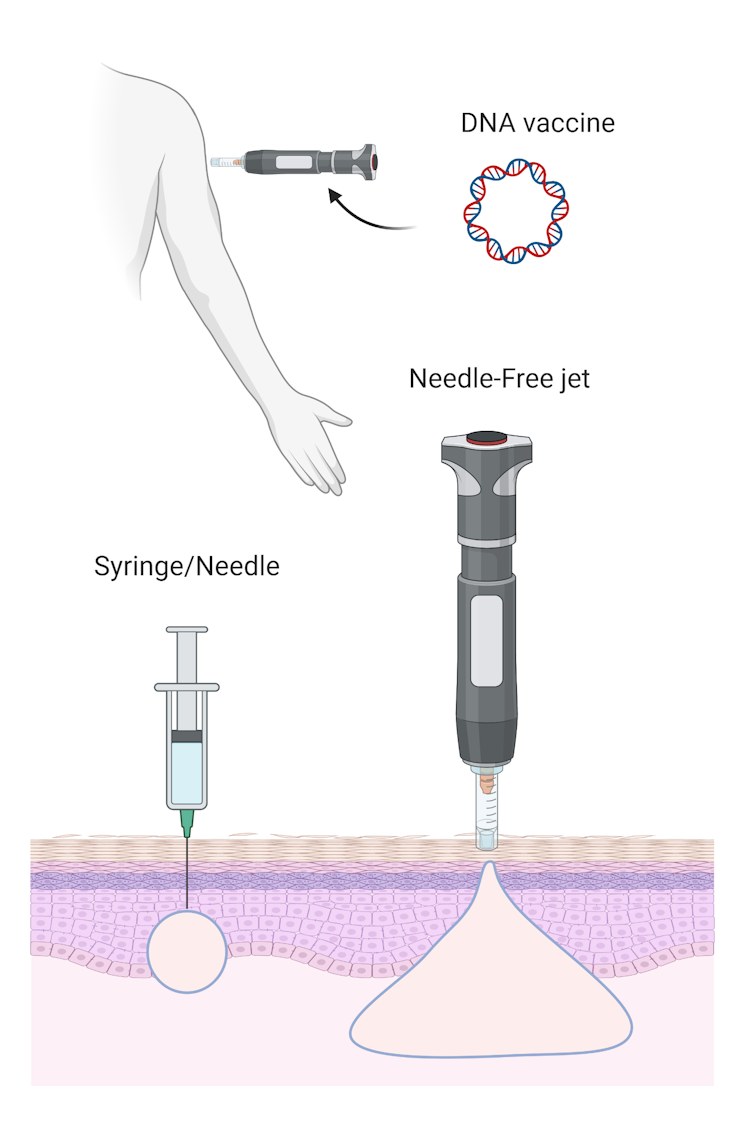

The third COVID-19 vaccine candidate uses DNA technology. A DNA-based vaccine works in a similar way to an mRNA vaccine. By producing the viral antigen inside us, mRNA and DNA vaccines teach our immune system to recognise the antigen should the virus invade in the future.

DNA vaccines have been under development for roughly the past 20 years. While they’re safe, their effectiveness remains in question. So the University of Sydney scientists are rethinking the way they’re delivered.

The previous DNA vaccines relied on a standard needle and syringe delivery, but the University of Sydney’s innovative approach uses a needle-free device. This method will deliver the vaccine using a “liquid jet” to penetrate our skin.

Needle-free delivery improves the distribution of the DNA vaccine deeper into the injected site, which can improve the vaccine’s effectiveness.

The University of Sydney group will aim to recruit 150 volunteers for a phase 1 clinical trial using the needle-free jet system.

The technology is already used to deliver some influenza vaccines. The technology may later be taken up for other COVID-19 vaccine candidates — including mRNA and proteins — if the needle-free system proves safe and effective.

Naturally, another key advantage of this approach is the absence of needles. This may improve vaccine acceptance in some groups, including children.

Further, DNA vaccines can be produced relatively easily in large quantities.

Investing in vaccine technologies will be essential for Australian public health, biosecurity and economic independence.

First, it’s unclear whether the current COVID-19 vaccines in phase 3 clinical trials will provide adequate protection. If they do, it’s similarly unclear how long that protection will last. Continued investments in a variety of vaccines at different stages of the development pipeline will ensure we have the best collection of vaccine technologies at our disposal.

Second, some of the development efforts could later yield a significant return on investment if they prove successful. Australia has an evolving biomanufacturing and biotechnology sector, and investment into these areas will benefit the next chapter of our country’s economic recovery.

Correction: this article previously stated it’s possible the scientists would combine both the mRNA and subunit protein vaccines into a one-shot product. This is not something the team at Monash University and/or the Doherty Institute are investigating as part of their forthcoming trial, so this has been removed.![]()

Harry Al-Wassiti, Bioengineer and Research Fellow, Monash University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

![]()

Menopausal Hormone Therapy - What Dose of Estrogen is Best?

Cardiovascular Benefits of GLP1s – New Evidence

Oral Contraceptive Pill in Teens

RSV and the Heart

Modified but kept in place

Eliminated entirely without replacement

Maintained as is

Completely replaced with an alternative system

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.

Menopause and MHT

Multiple sclerosis vs antibody disease

Using SGLT2 to reduce cardiovascular death in T2D

Peripheral arterial disease