Articles / Migrants delay care for heart attacks

writer

Associate Professor in Public Health, Torrens University Australia

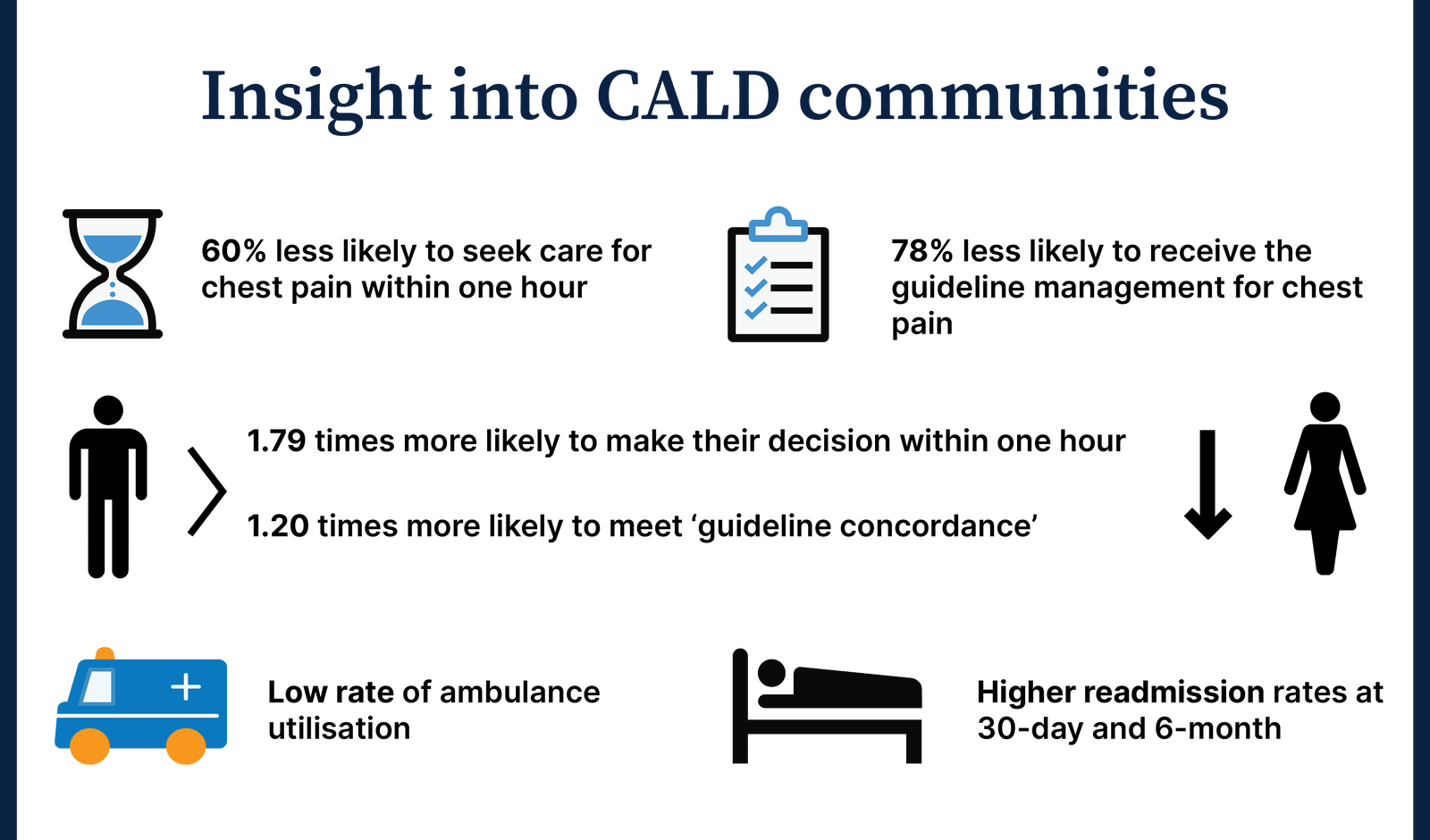

Our study of more than 600 patients who presented at a public hospital emergency department (ED) in South Australia with chest pain found some groups delayed seeking medical help and going to hospital much longer than others.

The median pre-hospital delay time for Sub-Saharan African migrants was six hours —compared with 3.7 hours across the whole group.

For migrants, this delay was overwhelmingly due to the patient’s decision to wait before seeking help (as opposed to, say, traffic problems in getting to a hospital, or an ambulance taking too long to arrive).

Specifically, the statistical analysis found this “decision time” to seek help accounted for up to 83% of the delay for migrants, compared to only 48% for Australian-born patients.

The top three longest delay times to seek medical care for chest pain compared to Australian born group were:

Our subsequent research has shown that certain factors may influence how long a migrant waits to seek help after chest pain first appears.

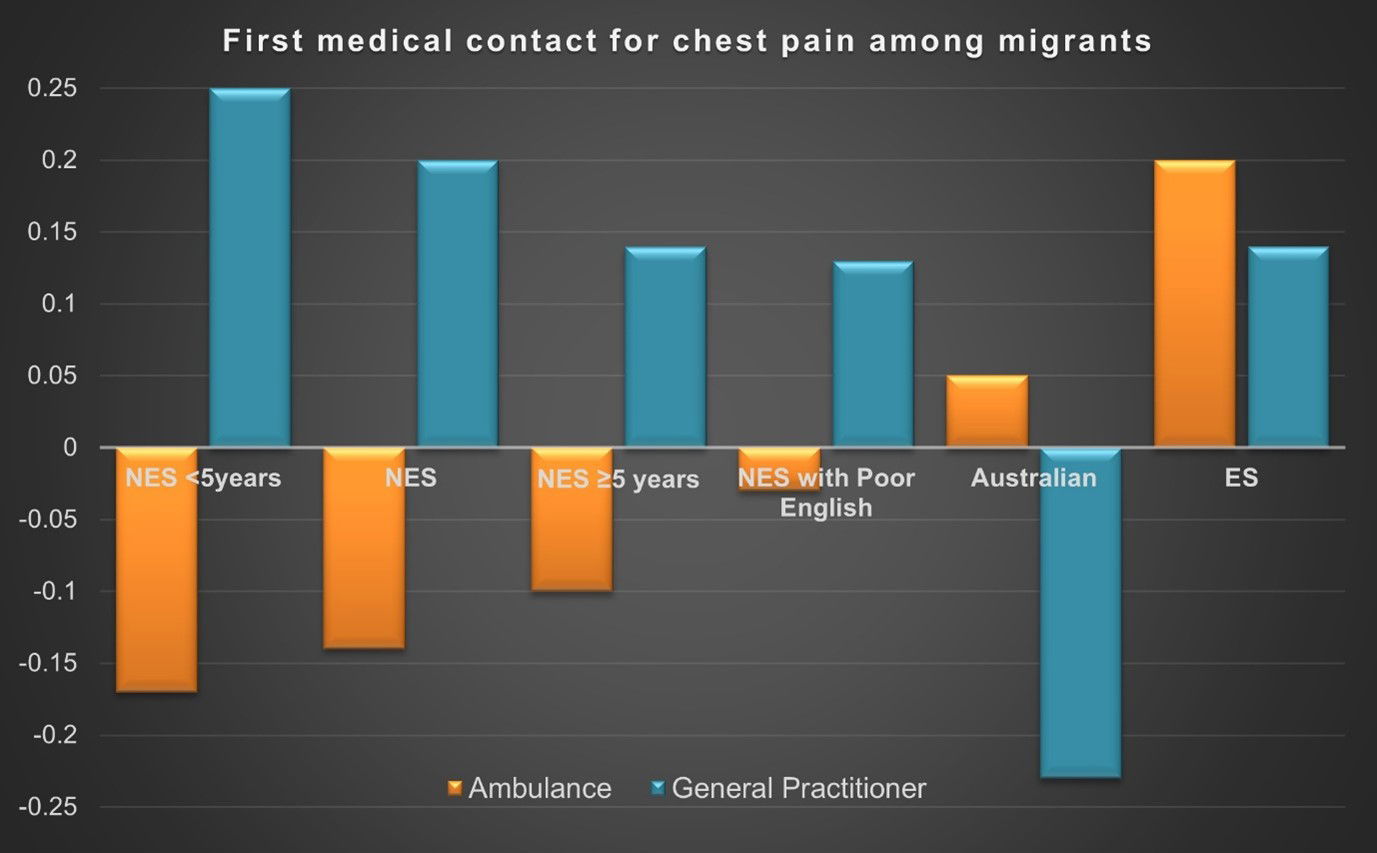

Non-English-speaking migrants are more likely to wait some hours before seeking help, while migrants from English-speaking backgrounds sought medical care more quickly.

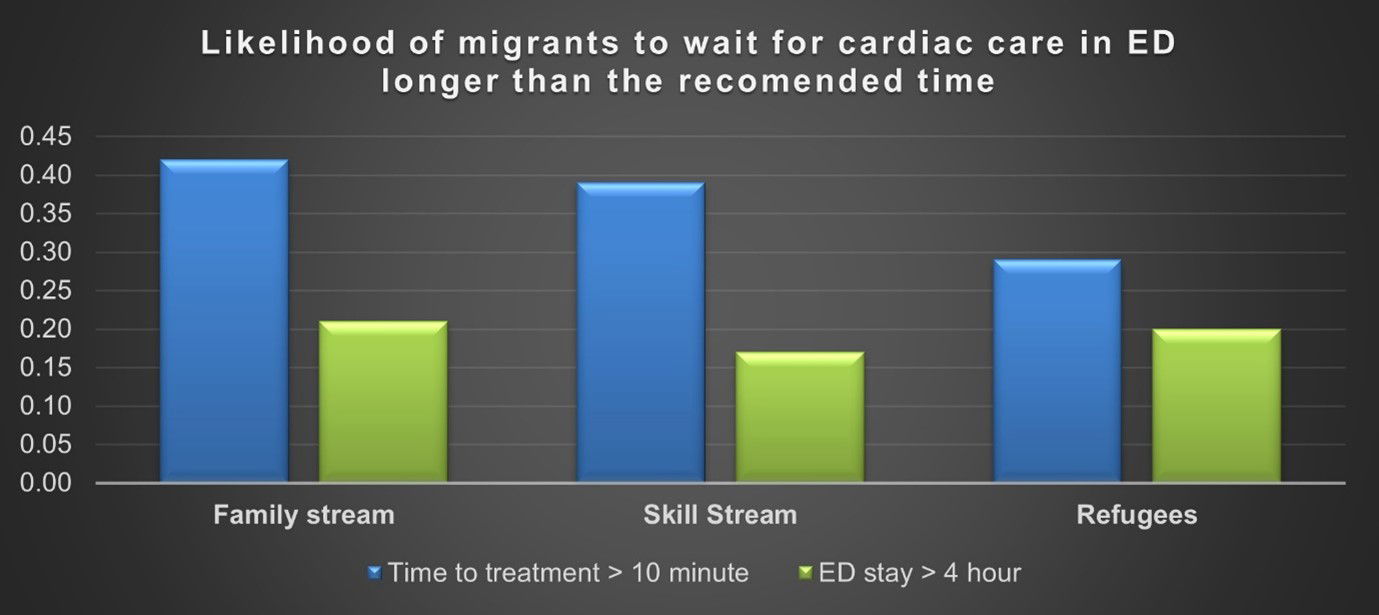

People on skilled visas are much more likely to take more than an hour before deciding to go to hospital, as are people on family visas (reuniting them with relatives already in Australia).

Those on humanitarian visas (refugees) tended to seek help sooner. This group is much more likely to have access to social supports and welfare services through special programs such as the Status Resolution Support Services or state-based refugee health services.

Migrants working in Australia on skilled visas, by contrast, may have delayed seeking help because they have no health insurance, are worried about their jobs or fear hefty ambulance fees or medical costs.

Once migrants decided to seek medical care for chest pain, they often did not call an ambulance straight away. Rather, they first opted to visit their family doctor or attempted to drive themselves to hospital. We found this was more common among migrants with limited English.

The reasons for delays are likely multifactorial.

“One migrant chef we spoke to experienced chest pain and dizziness but kept working because he was afraid, he might lose his job. He also worried that calling an ambulance would land him with a bill he couldn’t afford to pay.

Many people on family visas, particularly older migrants with limited English, worried about how to explain chest pain in an unfamiliar language and if they would be able to understand the doctor.

They often relied financially on younger family members and wanted to avoid being a “burden” to them by seeking help for their chest pain.

On the other hand, delay in reaching care could potentially be related to their interaction with health professionals. Our study reported a longer processing time in ED than the recommended time for migrant patients due to inefficient communications between clinicians and patients and family with limited English. In addition to language barriers, cultural competence also accounts for a delay in providing appropriate care to these groups.

Our long-running research has revealed some startling inequities— but key interventions would make a big difference. These include

Because so many migrants experiencing chest pain choose to visit their GP first, it’s important to explain the risks associated with delayed presentation for chest pain and delayed access to ambulance services to patients who are at risk of cardiac events.

Additionally, normalising cultural competence and cultural safety into the healthcare system and emphasising the need for culturally appropriate practice is essential. This cultural training must be included in all undergraduate training programs and in all GP postgraduate training models.

This final point is crucial. Most newly-arrived migrants may face a wait of between two and four years (depending on when they arrived) before they can fully access social security payments such as unemployment benefits.

These long waiting periods widen the gap and worsen the health inequities in our society.

This article has been adapted by the authors for a health professional audience. You can read the original Conversation article here: Many migrants wait hours after a heart attack to seek help. Here’s what needs to change (theconversation.com)

Co-Authors:

Dr. Philip Dalinjong

Senior Lecturer and Post-doctoral Fellow, Torrens University Australia

Emeritus Professor Justin Beilby

Academic and Research Management, Torrens University Australia

Professor John Glover

Public Health Information Development Unit, Torrens University

Postural Orthostatic Tachycardia Syndrome in Women

Panel Discussion on The Role of GLP-1 in the Management of CKD in T2D

Big Heads & Small Heads

Peanut Allergy

writer

Associate Professor in Public Health, Torrens University Australia

It should only change if there's clear evidence that a new model is better

It should remain independent and locally governed

It should be replaced with an untested national model

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.