Articles / Managing CKD with co-existing conditions

Along with information on new pharmacological therapies, the Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Management in Primary Care (5th edition) Handbook contains several other key updates around managing CKD in general practice.

CKD has a major impact on cardiovascular health. For people with CKD, the risk of dying from a cardiovascular event is up to 20 times greater than the risk of requiring dialysis or transplantation, for example.

The Handbook notes that:

How to assess CVD risk in patients with CKD

If you’re using the Australian CVD risk calculator to estimate a person’s cardiovascular risk, the Handbook recommends some adjustments in people with CKD.

1. “People with moderate to severe CKD (eGFR 30 mg/mmol) are considered to have pre-determined high risk of experiencing a cardiovascular event in the next 5 years (≥10% probability).”

2. “For people with eGFR 45-59 mL/ min/1.73m2 and/or uACR 3-30 mg/mmol, we recommend that their CVD risk is reclassified to a higher risk category to reflect albuminuria as a significant driver of CVD.”

The CVD risk guidelines include steps on how manage each risk category, while pages 26-28 of the updated CKD Handbook include colour coded management plans.

CKD and heart failure are common comorbidities, and heart failure is a leading cause of hospitalisation, morbidity and mortality in people with CKD.

Medication management of CKD in people with heart failure can be challenging due to the need to balance the differing effects of medications on the kidney and heart, says Breonny Robson General Manager of Clinical and Research at Kidney Heath Australia, who has been involved in developing the last four editions of the Handbook.

“We would recommend a ‘person-first’ approach where the overall wellbeing of the patient is considered. In some cases, a higher serum creatinine as a result of fluid management in heart failure may be acceptable if it means the patient can breathe normally,” Ms Robson says.

The Handbook includes a new section on managing CKD and heart failure, with detailed advice on how to safely prescribe medications.

RAS inhibitors, ARNIs, MRAs

Follow the usual advised precautions i.e. if eGFR declines by more than 25%, adjust the dose or stop the medication(s) temporarily, then restart at low doses and up-titrate slowly.

Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) should not be prescribed with an ACE inhibitor, nor should steroidal mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) be used together with non-steroidal MRAs.

Carefully monitor potassium.

SGLT2 inhibitors

SGLT2 inhibitor use is recommended to manage heart failure in patients with CKD of any stage provided indications for use are met. (The prescribing criteria differ depending on if the primary indication is for heart failure or CKD, so check pbs.gov.au for details).

IV iron

IV iron therapy is recommended for managing heart failure in patients with CKD of any stage, provided indications for its use are met.

Additionally, the Handbook recommends:

The Handbook also has a new section to guide GPs in managing hyperuricaemia, which commonly occurs with the metabolic syndrome often seen in people with CKD.

It advises that dietary approaches used to lower insulin resistance also reduce serum urate.

For managing gout in people with CKD, the Handbook notes therapy to lower uric acid may be indicated. It recommends:

Pain is common in patients with advanced CKD and kidney failure and can have a significant adverse effect on function and quality of life.

The Handbook recommends conducting a detailed history and examination to determine the type of pain syndrome and the following management strategies.

Localised pain

This can be treated with topical therapies such as herbal liniments or creams containing capsaicin or salicylates, or a gel based NSAID.

Severe pain

This necessitates systemic treatment, and the Handbook recommends following the WHO analgesic ladder.

Step 1: Non-opioid analgesia

Step 2: Weak opioids

Codeine and tramadol can be used with caution.

Step 3: Strong opioids

With appropriate dose adjustment, many short- and long-acting strong opioids can be used in people with CKD.

Treatment should be tailored in accordance with the person’s medical history and commenced in consultation with a specialist.

Morphine should be avoided in kidney failure but can be used at 75% of normal dose in people with an eGFR of 20-50 mL/min/ min/1.73m2.

Neuropathic pain

You can use the following medications as first-line treatments, or in conjunction with nociceptive pain management, as per the WHO analgesic ladder.

1. Gabapentinoids

2. Tricyclic antidepressants

3. Duloxetine (SNRI)

4. Other medications

Other medications that may be useful include lignocaine, mexiletine, and methadone, with guidance from a pain or palliative care team.

Pregnancy can be likened to a “CKD stress test”, the Handbook notes, and may unmask undiagnosed CKD or worsen known CKD. Pregnancies in people with CKD are high risk, with risk increasing along with worsening CKD stage.

While fertility declines as CKD stage worsens, ovulation can still occur even in advanced kidney failure and patients on dialysis, and an unplanned pregnancy can lead to some challenging decisions.

To support the best possible outcomes, the Handbook recommends:

In Australia, 17% of people are ‘late referrals’ to a kidney service and start dialysis within 90 days of first visiting a nephrologist, Ms Robson says.

“This allows little time for treatment choices for kidney failure to be explored and weighed up in the context of what is best for the individual.”

At the same time, kidney services around the country have limited capacity to see patients with very early-stage disease, she says, noting primary care providers play a key role in managing these patients.

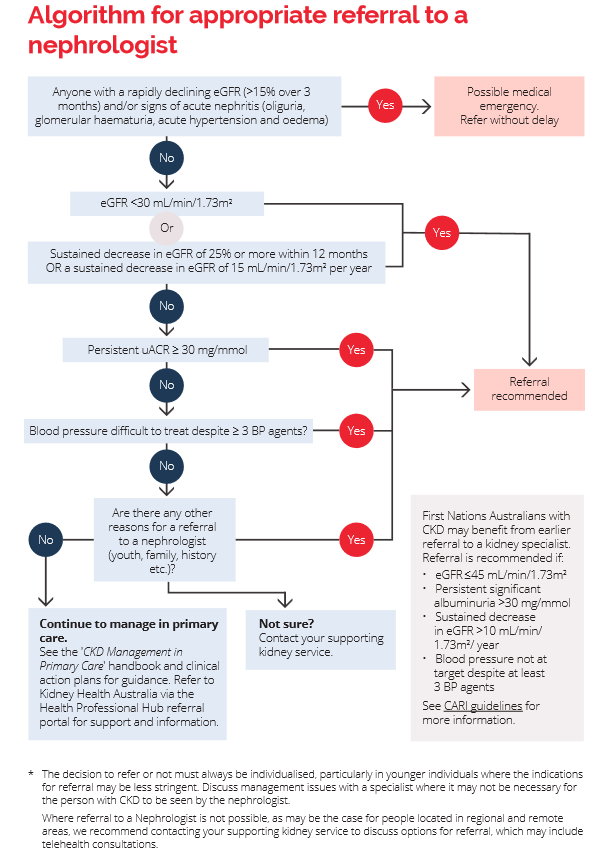

The Handbook has an algorithm to guide decisions about when to refer to a nephrologist.

Figure 3: Algorithm for appropriate referral of people with CKD to a Nephrologist

For more information:

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) Management in Primary Care | Kidney Health Australia

CKD medical management – key updates | Healthed

Allergen Introduction – Practical Tips for GPs

Oral Contraception Update

What do we do With High Triglycerides?

An Update on Heart Failure in Primary Care

Very overestimated

Moderately/slightly overestimated

Quite accurate

Moderately/slightly underestimated

Very underestimated

Listen to expert interviews.

Click to open in a new tab

Browse the latest articles from Healthed.

Once you confirm you’ve read this article you can complete a Patient Case Review to earn 0.5 hours CPD in the Reviewing Performance (RP) category.

Select ‘Confirm & learn‘ when you have read this article in its entirety and you will be taken to begin your Patient Case Review.