Read the latest articles relevant to your clinical practice, including exclusive insights from Healthed surveys and polls.

By reading selected clinical articles, you earn CPD in the Educational Activities (EA) category whenever you click the “Claim CPD” button and follow the prompts.

…colourful and playful in design, and may be confused with toys.All toys for children aged 36 months and below, including teething toys, are strictly regulated by Australian standards. As the ACCC warns, teething necklaces are unlikely to fulfil this requirement.

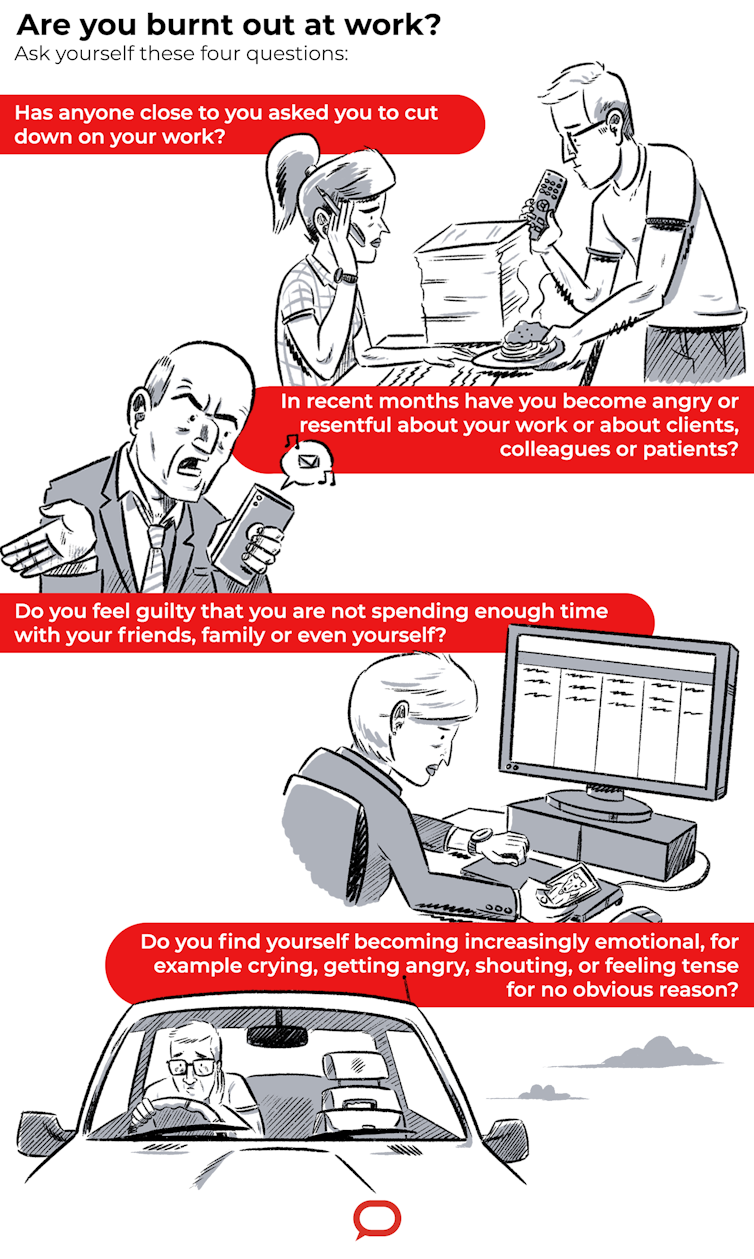

I dread coming to work. I find myself being short when dealing with staff and patients.French research on hospital emergency department staff found one in three (34%) were burnt out because of excessive workloads and high demands for care. Lawyers are another profession vulnerable to burnout. In a survey of 1,000 employees of a renowned London law firm, 73% of lawyers expressed feelings of burnout and 58% put this down to the need for a better work-life balance. No matter what job you do, if you are pushed beyond your ability to cope for long periods of time, you’re likely to suffer burnout.