Read the latest articles relevant to your clinical practice, including exclusive insights from Healthed surveys and polls.

By reading selected clinical articles, you earn CPD in the Educational Activities (EA) category whenever you click the “Claim CPD” button and follow the prompts.

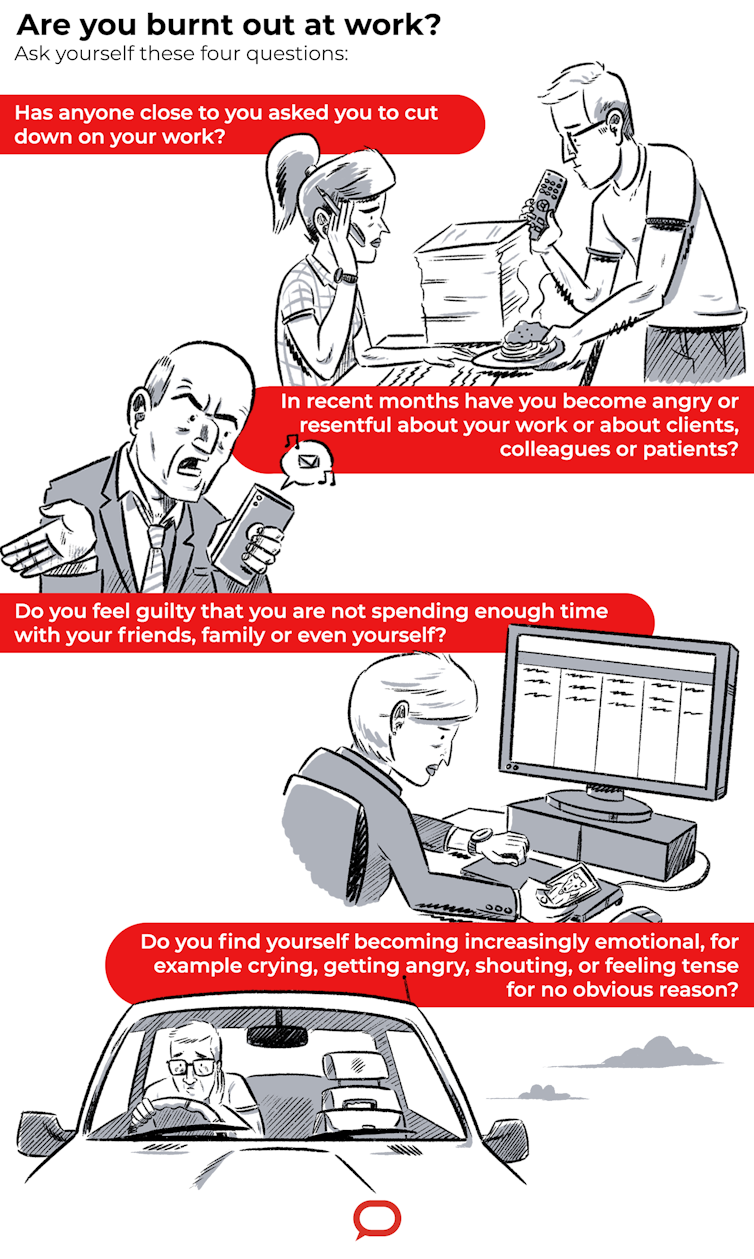

I dread coming to work. I find myself being short when dealing with staff and patients.French research on hospital emergency department staff found one in three (34%) were burnt out because of excessive workloads and high demands for care. Lawyers are another profession vulnerable to burnout. In a survey of 1,000 employees of a renowned London law firm, 73% of lawyers expressed feelings of burnout and 58% put this down to the need for a better work-life balance. No matter what job you do, if you are pushed beyond your ability to cope for long periods of time, you’re likely to suffer burnout.

“Ellen’s dying wish was that women of size make her death matter by advocating strongly for their health and not accepting that fat is the only relevant health issue.”How to know if this might be happening to you? When do you need to advocate for yourself? I studied the phenomenon of anti-fat stigma in Canadian primary care clinics for my PhD. Knowing how it happens might help.