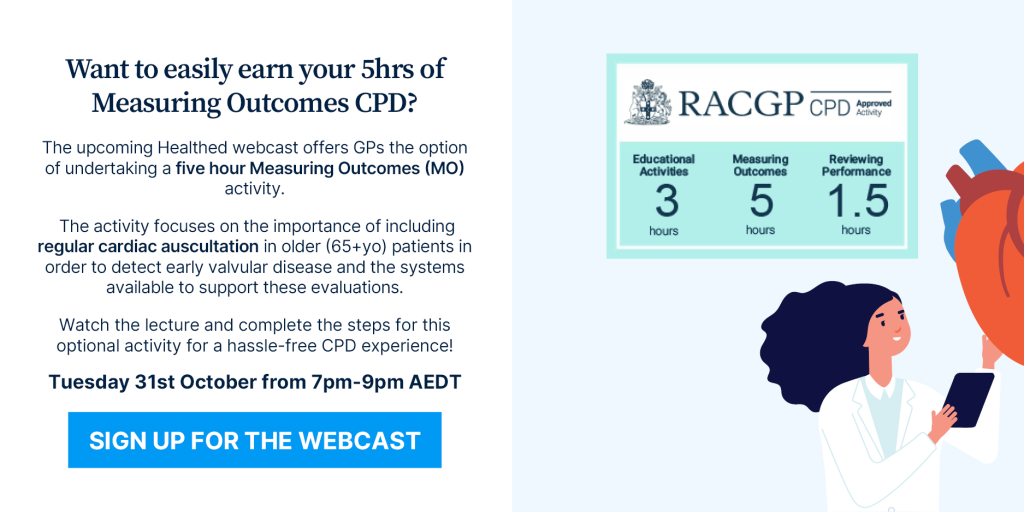

Page 108 of 129

PPIs for infant reflux a risk

It seemed such a godsend, didn’t it? Omeprazole for severe infant reflux. A massive improvement on the previous advice to elevate the head of the cot and nurse upright.

But since it first appeared in guidelines, there have been studies, reports and opinions cautioning against the overuse of PPIs citing everything from them being ineffectual to their potential to predispose the child to allergy.

Now it looks like there is yet another reason why we need to think again before prescribing a PPI for the distressed infant with reflux and their exhausted parents.

According to an article recently appearing in a JAMA network publication, recent study findings cast more doubt on the safety of this treatment option, suggesting that giving PPIs to infants less than six months of age is associated with a higher risk of bone fractures later in childhood.

The US researchers analysed data, including pharmacy outpatient data from over 850,000 children born within the Military Health Care System over a 12 year period. According to findings presented at a Pediatric Academic Societies Meeting earlier this year, children given a PPI in the first six months of their life had a 22% increased risk of fracture in the following 5-6 years. And if, for some reason they were also given a H2 blocker the risk jumped to 31%. Interestingly if they only received the H2 blocker there was no significant increase in fracture risk.

The study also showed the longer the duration of PPI use the greater the risk of fracture.

It is thought that the mechanism behind the increased fracture risk relates to the PPI-induced decrease in gastric acid causing a reduction in calcium absorption.

While the study is still going through the process of peer-review and is yet to be published, the study’s lead author, US Air Force Capt Laura Malchodi (MD) said the findings suggest increased caution should be exercised with regard these drugs.

“Our study adds to the growing body of evidence suggesting [acid-reducing] medications are not safe for children, especially very young children,” she told delegates.

“[PPIs] should only be prescribed to treat confirmed serious cases of more severe, symptomatic, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), and for the shortest length of time needed.”

Ref: JAMA published online Sept 29, 2017. Doi:10.1001/jama.2017.12160

Tags: Evidence-based Medicine, Paediatrics

October 4, 2017

Nobel prize winner: What they discovered and why it matters

Today, the “beautiful mechanism” of the body clock, and the group of cells in our brain where it all happens, have shot to prominence. The 2017 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine has been awarded to Jeffrey C. Hall, Michael Rosbash and Michael W. Young for their work on describing the molecular cogs and wheels inside our biological clock.

In the 18th century an astronomer by the name of Jean Jacques d’Ortuous de Marian noted his plants opening and closing their leaves with the cycle of light and dark, with the leaves opening towards the sun. Being an inquisitive chap, he placed the plants in constant darkness and observed that the daily opening and closing of the leaves continued even in the absence of sunlight – indicative of an internal clock.

Subsequent work by others also showed innate daily rhythms in other animals and plants, but the location and inner workings of the biological timing system remained a mystery.

Read more – Keeping time: how our circadian rhythms drive us

The discovery of a misfiring gene that resulted in disrupted daily rhythms in fruit flies (the unsung heroes of the story) gave the first hint. Over several years, Hall, Rosbash and Young uncovered the machinery of the biological clock.

It’s in your genes.

From the latin circa “about” and diem “a day”, circadian rhythms are internally driven cycles in all living things – including humans – that continue in the absence of external time cues. The sleep/wake cycle is one daily rhythm; core body temperature is another. While we have known since de Marian that physiological systems are controlled internally, the way in which the clock works was a mystery.

The biological clock’s cycle is generated by a feedback loop. Genes are activated which trigger the production of proteins. When protein levels build up to a critical threshold in the cells, the genes are switched off. The proteins then degrade over time to a point that allows the genes to switch back on, starting the cycle again. This takes about 24 hours.

But it isn’t just one gene doing all the work. Hall, Rosbach and Young found that many genes, proteins and regulators are involved in the complex machinery that keeps us ticking. Some molecules control the activation of genes, some are involved in the translation of light information from the eyes, and some govern the clock’s stability and precision, ensuring that it keeps ticking and remains in sync with the external environment.

While we already knew that the internally generated cycle existed, Hall, Rosbach and Young described the mechanisms by which the cycle is created and maintained at the molecular level. As a result of this work we now understand how internal rhythms remain synchronised with each other and with the external environment.

We are starting to understand the range of health challenges experienced by those who have to work against their internal clocks, such as shift workers. We can predict times of the day and night where alertness and performance are likely to be impaired and thus control the health and safety risks.

Read more: Power naps and meals don’t always help shift workers make it through the night

![]() And we can explain why, on the first morning after the start of daylight savings, waking up is so much harder. But don’t worry, the beautiful mechanism in your biological clock is designed to make adjustments based on the information it gets from the external environment, and those molecules will have you resynchronised in just a couple of days.

And we can explain why, on the first morning after the start of daylight savings, waking up is so much harder. But don’t worry, the beautiful mechanism in your biological clock is designed to make adjustments based on the information it gets from the external environment, and those molecules will have you resynchronised in just a couple of days.

Sally Ferguson, Research professor, CQUniversity Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

New Guidance For Assessment Of Lipids

Non-fasting specimens are now acceptable

Fasting specimens have traditionally been used for the formal assessment of lipid status (total, LDL and HDL cholesterol and triglycerides).1,2

In 2016, the European Atherosclerosis Society and the European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine released a joint consensus statement that recommends the routine use of non-fasting specimens for the assessment of lipid status.2

Large population-based studies were reviewed which showed that for most subjects the changes in plasma lipids and lipoproteins values following food intake were not clinically significant.

Maximal mean changes at 1–6 hours after habitual meals were found to be: +0.3 mmol/L for triglycerides; -0.2 mmol/L for total cholesterol; -0.2 mmol/L for LDL cholesterol; -0.2 mmol/L for calculated non-HDL cholesterol and no change for HDL cholesterol.

Additionally, studies have found similar or sometimes superior cardiovascular disease risk associations for non-fasting compared with fasting lipid test results.

There have also been large clinical trials of statin therapy, monitoring the efficacy of treatment using non-fasting lipid measurements. Overall, the evidence suggests that non-fasting specimens are highly effective in assessing cardiovascular disease risk and treatment responses.

Non-HDL cholesterol as a risk predictor

In the 2016 European joint consensus statement2 and in previously published guidelines and recommendations, the clinical utility of non-HDL cholesterol (calculated from total cholesterol minus HDL cholesterol) has been noted as a predictor of cardiovascular disease risk.

Moreover, this marker has been found to be more predictive of cardiovascular risk when determined in a non-fasting specimen.

What this means for your patients

The assessment of lipid status with a non-fasting specimen has the following benefits:

- No patient preparation is required, thereby reducing non-compliance

- Greater convenience with attendance for specimen collection at any time

- Reports are available for earlier review instead of potential delays associated with obtaining fasting results

Indications for repeat testing or a fasting specimen collection

For some patients, lipid testing on more than one occasion may be necessary in order to establish their baseline lipid status. It is also important to note that an assessment of lipid status carried out in the presence of any intercurrent illness may not be valid.

Conditions for which a fasting specimen collection is recommended2 include:

- Non-fasting triglyceride >5.0 mmol/L

- Known hypertriglyceridaemia followed in a lipid clinic

- Recovering from hypertriglyceridaemic pancreatitis

- Starting medications that may cause severe hypertriglyceridaemia (e.g., steroid, oestrogen, retinoid acid therapy)

- Additional laboratory tests are requested that require fasting or morning specimens (e.g., fasting glucose, therapeutic drug monitoring)

Lipid reference limits and target levels for treatment are under review

The chemical pathology community in Australia is currently reviewing all relevant publications in order to implement a consensus approach to reporting and interpreting lipid results. This includes the guidelines for management of absolute cardiovascular disease risk developed by the National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance (NVDPA).3

Further information

- Absolute cardiovascular disease risk calculator is available atwww.cvdcheck.org.au

- If familial hypercholesterolaemia is suspected, e.g. LDL cholesterol persistently above 5.0 mmol/L in adults, then advice about diagnosis and management is available at www.athero.org.au/fh

References

- Rifai N, et al. Non-fasting Sample for the Determination of Routine Lipid Profile: Is It an Idea Whose Time Has Come? ClinChem 2016;62: 428-35.

- Nordestgaard BG, et al. Fasting Is Not Routinely Required for Determination of a Lipid Profile: Clinical and Laboratory Implications Including Flagging at Desirable Concentration Cutpoints -A Joint Consensus Statement from the European Atherosclerosis Society and European Federation of Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine. Clin Chem 2016;62: 930-46.

- National Vascular Disease Prevention Alliance, Absolute cardiovascular disease management, Quick reference guide for health professionals

General Practice Pathology is a new fortnightly column each authored by an Australian expert pathologist on a topic of particular relevance and interest to practising GPs.

The authors provide this editorial, free of charge as part of an educational initiative developed and coordinated by Sonic Pathology.

Tags: Cardiology, Evidence-based Medicine

September 27, 2017

Obesity Surgery – Worth The Money

For most patients in Australia, obesity surgery is an expensive exercise. The surgery alone is likely to see you out of pocket to the tune of several thousand at least. And then there’s the time off work, specialist appointments, follow-up etc etc.

So you can understand patients being hesitant about the prospect. And then there’s the worry about effectiveness. Will it work? And if so for how long?

Well, new research, published in The New England Journal of Medicine goes a long way to alleviating those fears.

The prospective US study, showed that not only did more than 400 severely obese patients who underwent gastric bypass surgery lose a significant amount of weight but that weight loss and the health benefits obtained because of it, were sustained 12 years later.

Two years after undergoing the Roux-en-Y surgery, these patients had lost an average of 45kg. Over the following decade there was some weight gain, but at the end of the 12 years the average weight loss from baseline was still a massive 35kg.

The impressiveness of this statistic is put into perspective by researchers who compared this cohort with a similar number of severely obese people who had sought but did not undergo gastric bypass. Over the duration of the study this group lost an average of only 2.9kg. And another group, also obese patients who had not sought surgery lost no weight at all on average over this time period.

What is even more significant is the difference in morbidity associated with the surgery. The researchers found that of the patients who had type 2 diabetes at baseline, 75% no longer had the disease at two years. And despite the progressive nature of type 2 diabetes, 51% were still diabetes-free at 12 years. In addition, the surgery group had higher remission rates and lower incidence rates of hypertension and lipid disorders.

“This study showed long-term durability of weight loss and effective remission and prevention of type 2 diabetes, hypertension and dyslipidaemia after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass,” the study authors concluded.

Even though this surgery is done less commonly in Australia than laparoscopic procedures, the reality is that bariatric surgery, for the most part represents enormous value for severely obese patients. The dramatic results and the significant health benefits will no doubt increase pressure on the government and private health insurers to improve access to what could well be described as life-changing surgery.

Ref:

NEJM 2017; 377: 1143-1155. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700459

Tags: Gastroenterology, Surgery

Stress and social media fuel mental health crisis among UK girls

Girls and young women are experiencing a “gathering crisis” in their mental health linked to conflict with friends, fears about their body image and pressures created by social media, experts have warned.

Rates of stress, anxiety and depression are rising sharply among teenage girls in what mental health specialists say is a “deeply worrying” trend that is far less pronounced among boys of the same age. They warn that the NHS lacks the resources to adequately tackle the problem.

New NHS data obtained by the Guardian reveals that the number of times a girl aged 17 or under has been admitted to hospital in England because of self-harmhas jumped from 10,500 to more than 17,500 a year over the past decade – a rise of 68%. The jump among boys was much lower: 26%.

Cases of self-poisoning among girls – ingesting pills, alcohol or other chemical substances – rose 50%, from 9,700 to 14,600 between 2005-06 and 2015-16. Similarly, the number of girls treated in hospital after cutting themselves quadrupled, from 600 to 2,400 over the same period, NHS Digital figures show.

Rising levels of “body dissatisfaction” – insecurity and low self-esteem about their appearance – have been identified as driving the unprecedented levels of mental turmoil in young women.

“There is a growing crisis in children and young people’s mental health, and in particular a gathering crisis in mental distress and depression among girls and young women,” said Dr Bernadka Dubicka, the chair of the child and adolescent faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatrists. “Emotional problems in young girls have been significantly, and very worryingly, on the rise over the past few years.”

Increasing numbers of academic studies are finding that mental health problems have been soaring among girls over the past 10 – and in particular five – years, coinciding with the period in which young people’s use of social media has exploded.

Source: The Guardian

How long do anxiety patients need medication?

It is well-known that when a patient with depression is commenced on antidepressants and they are effective, they should continue them for at least a year to lower their risk of relapse. The guidelines are pretty consistent on that point.

But what about anxiety disorders?

Along with cognitive behavioural therapy, antidepressants are considered a first-line option for treating anxiety conditions such as generalised anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder and post-traumatic disorder. Antidepressants have been shown to generally effective and well-tolerated in treating these illnesses.

But how long should they be used in order to improve long-term prognosis?

Internationally, guidelines vary in their recommendations. If the treatment is effective the advice has been to continue treatment for variable durations (six to 24 months) and then taper the antidepressant, but this has been based on scant evidence.

To clarify this recommendation, Dutch researchers conducted a meta-analysis of 28 relapse prevention trials in patients with remitted anxiety disorders.

Their findings, recently published in the BMJ, support the continuation of pharmacotherapy.

“We have shown a clear benefit of continuing treatment compared with discontinuation for both relapse… and time to relapse”, the authors stated.

In addition, the researchers found the relapse risk was not significantly influenced by the type of anxiety disorder, whether the antidepressant was tapered or stopped abruptly or whether the patient was receiving concurrent psychotherapy

However, because of the duration of the studies included in the meta-analysis, only the advice to continue antidepressants for at least a year could be supported by evidence. After this, the researchers said there was no evidence-based advice that could be given.

“[However] the lack of evidence after this period should not be interpreted as explicit advice to discontinue antidepressants after one year,” they said.

The researchers suggested that those guidelines that advise antidepressant should be tapered after the patient has achieved a sustained remission should be revised.

In fact, they said, there were both advantages and disadvantages to continuing treatment beyond a year, and more research was needed to help clinicians assess an individual’s risk of relapse. This is especially important as anxiety disorders are generally chronic and there have been indications that in some patients, the antidepressant therapy is less effective when reinstated after a relapse.

“When deciding to continue or discontinue antidepressants in individual patients, the relapse risk should be considered in relation to side effects and the patient’s preferences,” they concluded.

Ref: BMJ 2017;358:j392 doi:10.1136/bmj:j3927

Tags: Psychiatry

September 20, 2017

How much sleep do children really need?

How much sleep, and what type of sleep, do our children need to thrive?

In parenting, there aren’t often straightforward answers, and sleep tends to be contentious. There are questions about whether we are overstating children’s sleep problems. Yet we all know from experience how much better we feel, and how much more ready we are to take on the day, when we have had an adequate amount of good quality sleep.

I was one of a panel of experts at the American Academy of Sleep Medicine to review over 800 academic papers examining relationships between children’s sleep duration and outcomes. Our findings suggested optimal sleep durations to promote children’s health. These are the optimal hours (including naps) that children should sleep in every 24-hour cycle.

And yet these types of sleep recommendations are still controversial. Many of us have friends or acquaintances who say that they can function perfectly on four hours of sleep, when it is recommended that adults get seven to nine hours per night.

Optimal sleep hours: The science

We look for science to support our recommendations. Yet we cannot deprive young children of sleep for prolonged periods to see whether they have more problems than those sleeping the recommended amounts.

Some experiments have been conducted with teenagers when they have agreed to short periods of sleep deprivation followed by regular sleep durations. In one example, teenagers who got inadequate sleep time had worse moods and more difficulty controlling negative emotions.

Those findings are important because children and adolescents need to learn how to regulate their attention and manage their negative emotions and behaviour. Being able to self-regulate can enhance school adjustment and achievement.

With younger children, our studies have had to rely on examining relationships between their sleep duration and quality of their sleep and negative health outcomes. For example, when researchers have followed the same children over time, behavioural sleep problems in infancy have been associated with greater difficulty regulating emotions at two to three years of age.

Persistent sleep problems also predicted increased difficulty for the same children, followed at two to three years of age, to control their negative emotions from birth to six or seven years and for eight- to nine-year-old children to focus their attention.

Optimal sleep quality: The science

Not only has the duration of children’s sleep been demonstrated to be important but also the quality of their sleep. Poor sleep quality involves problems with starting and maintaining sleep. It also involves low satisfaction with sleep and feelings of being rested. It has been linked to poorer school performance.

Kindergarten children with poor sleep quality (those who take a long time to fall asleep and who wake in the night) demonstrated more aggressive behaviour and were represented more negatively by their parents.

Infants’ night waking was associated with more difficulties regulating attention and difficulty with behavioural control at three and four years of age.

From diabetes to self-harm

The Consensus Statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine suggested that children need enough sleep on a regular basis to promote optimal health.

The expert panel linked inadequate sleep duration to children’s attention and learning problems and to increased risk for accidents, injuries, hypertension, obesity, diabetes and depression.

Insufficient sleep in teenagers has also been related to increased risk of self-harm, suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts.

Parent behaviours

Children’s self-regulation skills can be developed through self-soothing to sleep at settling time and back to sleep after any night waking. Evidence has consistently pointed to the importance of parents’ behaviours not only in assisting children to achieve adequate sleep duration but also good sleep quality.

Parents can introduce techniques such as sleep routines and consistent sleep schedules that promote healthy sleep. They can also monitor children to ensure that bedtime is actually lights out without electronic devices in their room.

![]() In summary, there are recommended hours of sleep that are associated with better outcomes for children at all ages and stages of development. High sleep quality is also linked to children’s abilities to control their negative behaviour and focus their attention — both important skills for success at school and in social interactions.

In summary, there are recommended hours of sleep that are associated with better outcomes for children at all ages and stages of development. High sleep quality is also linked to children’s abilities to control their negative behaviour and focus their attention — both important skills for success at school and in social interactions.

Wendy Hall, Professor, Associate Director Graduate Programs, UBC School of Nursing, University of British Columbia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Tags: Neurology, Paediatrics

‘Microbiomes’ may hold key to kids’ ear infections

Recurrent ear infections are the bane of many children—and the parents who have to deal with their care. Now, research suggests that naturally occurring, “helpful” bacterial colonies in the ear—called “microbiomes” by scientists—may help decide a person’s vulnerability to these infections.

“The children and adults with normal middle ears differed significantly in terms of middle ear microbiomes,” concluded a team of Japanese researchers led by Dr. Shujiro Minami of the National Institute of Sensory Organs in Tokyo.

One expert in the United States said the study is an important first step in learning more about ear infections.

“What this study tells us is that we have lots of bacteria living in our middle ears, regardless of whether or not we have chronic ear infections,” said Dr. Sophia Jan, chief of pediatrics at Cohen Children’s Medical Center in New Hyde Park, N.Y. “The study suggests that some kinds of bacteria don’t seem to cause us problems when present in our middle ear.”

However, “we still have a lot to learn before we can apply this research to the treatment or prevention of chronic ear infections,” she added. “We don’t know if the bacteria found in ‘healthy’ ears can be problematic, for example, if present in higher quantities.”

Ear infections “are the most common reason parents bring their child to a doctor,” according to the U.S. National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders. These bacterial infections—called otitis media—typically start in the middle ear, and 5 out of 6 kids will develop at least one ear infection by the time they turn 3.

In the new study, Minami and colleagues wanted to see what role the ear’s microbiome might play in these outbreaks. To do so, they took swab samples of the middle ears of 155 children and adults who were having ear surgery due to recurrent ear infections (88 cases) or some other condition.

Among patients with a history of ear infections, the researchers found significant differences in the makeup of microbial communities for people with active (“wet”) or inactive (“dry”) inflammation.

In fact, people whose ear infection was dormant “had similar middle ear microbiomes as the normal [no ear infection] middle ears group,” the researchers said.

Source: Medical Xpress

Could It Be Endometriosis?

Endometriosis, or more particularly diagnosis of endometriosis is often a challenge in general practice.

When should you start investigating a young girl with painful periods? Is it worth investigating or should we just put them on the Pill? At what point should these young women be referred?

Consequently, the most recent NICE guidelines on the diagnosis and management of endometriosis, published in the BMJ will be of interest to any GP who manages young women.

According to the UK guidelines, there is commonly a delay of up to 10 years between the development of symptoms and the diagnosis of endometriosis, despite the condition affecting an estimated 10% of women in the reproductive age group.

Endometriosis should be suspected in women who have one or more of the following symptoms:

- chronic pelvic pain

- period pain that is severe enough to affect their activities

- deep pain associated with or just after sex

- period-related bowel symptoms such as painful bowel movements

- period-related urinary symptoms such as dysuria or even haematuria

Sometimes it can be worthwhile to get the patient to keep a symptom diary especially if they are unsure if their symptoms are indeed cyclical. Women who present with infertility and a history of one or more of these symptoms should also be suspected as having endometriosis.

Investigations

With regard investigations, the guidelines importantly state that endometriosis cannot be ruled out by a normal examination and pelvic ultrasound. Nonetheless after abdominal and pelvic examination, transvaginal ultrasound should be the first investigation to identify endometriomas and deep endometriosis that has affected other organs such as the bowel or bladder. Transabdominal ultrasounds are a worthwhile alternative in women for whom a transvaginal ultrasound is not appropriate.

MRI might be appropriate as a second line investigation but only to determine the extent of the disease. It should not be used for initial diagnosis. Similarly, the serum CA-125 is an inappropriate and unreliable diagnostic test.

Diagnostic laparoscopy is reserved for women with suspected endometriosis who have a normal ultrasound.

Treatment

If the symptoms of endometriosis can’t be adequately controlled with analgesia, the guidelines recommend hormonal treatment with either the combined oral contraceptive pill or progestogen. Women need to be aware that this will reduce pain and will have no permanent negative effect on fertility.

Surgical options to treat endometriosis need to be considered in women whose symptoms remain intolerable despite hormonal treatment, if the endometriosis is extensive involving other organs or if fertility is a priority and it is suspected that the endometriosis might be affecting the woman’s ability to fall pregnant.

All in all, these guidelines from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists don’t offer much in the way of new treatments but they do provide a framework to help GPs manage suspected cases of endometriosis and hopefully reduce that time delay between symptom-onset and diagnosis.

BMJ 2017; 358: j3935 doi: 10.1136/bmj.j3935

Tags: Diagnostics, Obstetrics and Gynaecology

September 13, 2017

New Autism Guidelines Miss The Mark

The first national guidelines for diagnosing autism were released for public consultation last week. The report by research group Autism CRC was commissioned and funded by the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) in October 2016.

The NDIS has taken over the running of federal government early intervention programs that provide specialist services for families and children with disabilities. In doing so, they have inherited the problem of diagnostic variability. Biological diagnoses are definable. The genetic condition fragile X xyndrome, for instance, which causes intellectual disability and development problems, can be diagnosed using a blood test.

Autism diagnosis, by contrast, is imprecise. It’s based on a child’s behaviour and function at a point in time, benchmarked against age expectations and comprising multiple simultaneous components. Complexity and imprecision arise at each stage, implicit to the condition as well as the process. So, it makes sense the NDIS requested an objective approach to autism diagnosis.

Read more: The difficulties doctors face in diagnosing autism

The presumption of the Autism CRC report is that standardising the method of diagnosis will address this problem of diagnostic uncertainty. But rather than striving to secure diagnostic precision in the complexity and imprecision of the real world, a more salient question is how best to help children when diagnostic uncertainty is unavoidable.

What’s in the report?

The report recommends a two-tiered diagnostic strategy. The first tier is used when a child’s development and behaviour clearly meet the diagnostic criteria.

The process proposed does not differ markedly from current recommended practice, with one important exception. Currently, the only professionals who can “sign off” on a diagnosis of autism are certain medical specialists such as paediatricians, child and adolescent psychiatrists, and neurologists. The range of accepted diagnosticians has now been expanded to include allied health professionals such as psychologists, speech pathologists and occupational therapists.

This exposes the program to several risks. Rates of diagnosed children may further increase with greater numbers of diagnosticians. Conflict of interest may occur if diagnosticians potentially receive later benefit as providers of funded treatment interventions. And while psychologists and other therapists may have expertise in autism, they may not necessarily recognise the important conditions that can present similarly to it, as well as other problems the child may have alongside autism.

The second recommended tier of diagnosis is for complex situations, when it is not clear a child meets one or more diagnostic criteria. In this case, the report recommends assessment and agreement by a set of professionals – known as a multidisciplinary assessment. This poses important challenges:

- Early intervention starts early. Multidisciplinary often means late, with delays on waiting lists for limited services. This is likely to worsen if more children require this type of assessment.

- Multidisciplinary assessments are expensive. If health systems pay, capacity to subsequently help children in the health sector will be correspondingly reduced.

- Groups of private providers may set up diagnostic one-stop shops. This may inadvertently discriminate against those who can’t pay and potentially bias towards diagnosis for those who can.

- Multidisciplinary assessments discriminate against those in regional and rural areas, where professionals are not readily available. Telehealth (consultation over the phone or computer) is a poor substitute for direct observation and interaction. Those in rural and regional areas are already disadvantaged by limited access to intervention services, so diagnostic delays present an additional obstacle.

A diagnostic approach reflects a deeper, more fundamental problem. Methodological rigour is necessary for academic research validity, with the assumption autism has distinct and definable boundaries.

But consider two children almost identical in need. One just gets over the diagnostic threshold, the other not. This may be acceptable for academic studies, but it’s not acceptable in community practice. An arbitrary diagnostic boundary does not address complexities of need.

We’re asking the wrong question

The federal government’s first initiative to fund early intervention services for children diagnosed with autism was introduced in 2008. The Helping Children With Autism program provided A$12,000 for each diagnosed child, along with limited services through Medicare.

The Better Start program was introduced later in 2011. Under Better Start, intervention programs also became available for children diagnosed with cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, fragile X syndrome and hearing and vision impairments.

While this broadened the range of disabilities to be funded, it did not address the core problem of discrimination by diagnosis. This is where children who have equal needs but who for various reasons aren’t officially diagnosed are excluded from support services. Something is better than nothing, however, and these programs have helped about 60,000 children at a cost of over A$400 million.

Yet the NDIS now also faces a philosophical challenge. The NDIS considers funding based on a person’s ability to function and participate in life and society, regardless of diagnosis. By contrast, entry to both these early intervention programs is determined by diagnosis, irrespective of functional limitation.

While funding incentives cannot change prevalence of fragile X syndrome in our community (because of its biological certainty), rates of autism diagnoses have more than doubled since the Helping Children with Autism program began in 2008. Autism has become a default consideration for any child who struggles socially, behaviourally, or with sensory stimuli.

Clinicians have developed alternative ways of thinking about this “grey zone” problem. One strategy is to provide support in proportion to functional need, in line with the NDIS philosophy.

Another strategy is to undertake response-to-intervention. This is well developed in education, where support is provided early and uncertainty is accepted. By observing a child’s pattern and rate of response over time, more information emerges about the nature of the child’s ongoing needs.

The proposed assessment strategy in the Autism CRC report addresses the question, “does this child meet criteria for autism?”. This is not the same as “what is going on for this child, and how do we best help them?”. And those are arguably the more important questions for our children.

![]() This article was co-authored by Dr Jane Lesslie, a specialist developmental paediatrician. Until recently she was vice president of the Neurodevelopmental and Behavioural Paediatric Society of Australasia.

This article was co-authored by Dr Jane Lesslie, a specialist developmental paediatrician. Until recently she was vice president of the Neurodevelopmental and Behavioural Paediatric Society of Australasia.

Michael McDowell, Associate Professor, The University of Queensland

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Tags: Diagnostics, Public Health

Assassination by pacemaker: Australia needs to do more to regulate internet-connected medical devices

In the future, people are going to be just a little bit cyborg. We’ve accepted hearing aids, nicotine patches and spectacles, but implanted medical devices that are internet-connected present new safety challenges. Are Australian regulators keeping up?

A global recall of pacemakers has sparked new fears and splashy headlines about hacked medical devices. But the next 20 years of medicine will normalise the use of intelligent implants to control pain, provide data for diagnostic purposes and supplement ailing organs, which means we need proper security as well as access in case of emergency.

Read More: Three reasons why pacemakers are vulnerable to hacking

Pharmaceuticals and medical devices in Australia are regulated by the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA), an arm of the national Health Department.

Can we rely on Australia’s medical devices regime? Recurrent criticisms by parliamentary committees and government inquiries suggest the regulator may be struggling.

The job of the TGA

The TGA regulates medical devices such as stents, pacemakers, joint implants, breast implants, and the controversial vaginal mesh that has featured recently in the media (and a Senate inquiry) over claims it seriously injured patients.

The role of the TGA is vital, because defective devices can result in injury or death. They have a major cost for the public health system and affect patient quality of life. They often result in litigation, sometimes with billion-dollar settlements.

In undertaking its mission, the TGA looks to information from manufacturers and distributors, from overseas regulators and its own staff.

Like counterparts such as the US Food and Drug Administration, TGA staff are under pressure to get products into the marketplace and reduce “red tape”.

The TGA and cybersecurity

Wireless medical devices need greater security than, say, an internet-connected fridge. It is axiomatic that they must work.

We need to ensure that information provided by the devices is safeguarded and that control of the devices – implantable or otherwise – is not compromised.

To do that, we can use existing tools such as robust passwords, encryption and systems design. It also requires product vendors and practitioners to avoid negligence. Regulators must proactively foster and enforce standards.

Put simply, bodies like the TGA need to deal with software rather than simply bits of metal and plastic. It is unclear whether the TGA has the expertise or means to do so.

Solutions, not panic

The past decade has seen a succession of inquiries into the TGA, including the 2015 Sansom Review and 2012 Senate PIP Inquiry. Each has demonstrated that the TGA is not always keeping up with its task.

Problems are ongoing: think defective joint implants, breast implants and vaginal mesh. But there are some potential paths towards improvement.

Accountability

One solution is to ensure the TGA is more accountable.

Currently, if someone wishes to bring a claim alleging a device was improperly permitted, the TGA has immunity from civil litigation about regulatory failure.

Removal of immunity will force it to focus on outcomes. That can be reinforced by giving it independence from the Department of Health, making it report direct to Parliament and ensuring the openness emphasised by the Pearce Inquiry.

Regulatory capture

Medical products regulation in Australia has been a matter of penny wise, pound poor. The TGA is funded by fees from the manufacturers and distributors that it regulates, in addition to some government funding.

It needs a discrete budget that recoups costs but is not dependent on companies that complain regulation is expensive. It needs enough resources to do its job well in the emerging age of the internet of things, including access to independent expertise regarding cybersecurity and devices.

A device register

How many devices have been implanted and how many removed? The lack of data about medical devices is a problem.

The government has so far not embraced recommendations for a comprehensive device register, one allowing timely identification of what was implanted and by whom.

Read More: Vaginal mesh controversy shows collective failure of the TGA and Australia’s specialists

Such a register would provide a means for determining problems with devices or medical practice. We need timely, consistent reporting of problems on a mandatory basis, as well as recall and transparent investigation of what went wrong.

Disclosure of interests

The inquiry into vaginal mesh revealed the WA Branch of Australian Medical Association had a financial interest in a device that may have seriously affected numerous women.

There must be full disclosure of such interests, with meaningful sanctions where disclosure has not been made. This requires action by the TGA, professional bodies and the government.

So, what about assassination by wireless pacemaker?

The cybersecurity of medical devices is a matter for everyone.

We need the TGA to work with manufacturers, distributors and health professionals to mandate best practice. Should, for example, manufacturers and practitioners ensure that implants do not rely on default passwords that are easily crackable? What about access by emergency services?

![]() There is a fundamental need to develop and enforce a national safety standard regarding all wireless implants. For that we need thoughtful policy, not just headlines.

There is a fundamental need to develop and enforce a national safety standard regarding all wireless implants. For that we need thoughtful policy, not just headlines.

Bruce Baer Arnold, Assistant Professor, School of Law, University of Canberra

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

‘Mind-body’ healing: Success of placebo trials challenges medical thinking

Damien Finniss was working as a physiotherapist when, on a still winter’s afternoon in 2001, he set up his treatment table in a shed at the perimeter of a Sydney footy ground.

As players came off with sundry aches – a pulled hammy here, a calf strain there – Finniss ministered to them with therapeutic ultrasound, a device that applies sound waves to the injured area with a handheld probe.

“I treated in excess of five or six athletes during the training session. I’d treat them for five or 10 minutes and they’d say ‘I feel much better’ and run back on to the training field,” recalls Finniss, now a medical doctor and Associate Professor at the University of Sydney’s Pain Management and Research Institute.

“But, at the end of the session, I realised that I’d, basically, had the machine turned off.”

Forgetting to switch his device on at the wall, to no apparent detriment, was a light bulb moment that led Finniss to become a leading researcher on the placebo effect – the power of treatments with no active ingredients to heal the sick, sometimes dramatically.

“I’ve seen people who have had terrible arthritic pain for five or 10 years, receive a placebo injection, stand up, and walk straight out,” says Finniss, referring to patients in a clinical trial he ran.

Indeed, sham treatments in the form of sugar pills, fake creams and saline injections have delivered relief to people with depression, psoriasis and Parkinson’s disease, to name a few.

But the placebo has an image problem which has made it something of a dirty little secret in the medical profession.

It was widely thought that, for a placebo to work, doctors had to deceive patients that they were getting the real deal, and that’s problematic for a profession keen to promote informed consent.

But a new study casts doubt on whether deceit is necessary at all and, along with a swag of research showing some remarkable placebo effects, raises big questions about whether placebos should now enter the mainstream as a legitimate item for doctors to prescribe.

Led by Oxford University’s Jeremy Howick, the study examined five trials of so-called “open label” placebos, in which participants are told they are getting a dummy pill, sometimes with the advice that it has been shown to work through a “mind-body” healing mechanism.

And for conditions that included lower back pain, irritable bowel syndrome, hay fever, depression and ADHD, giving a placebo honestly, the researchers concluded, worked.

Source: The Sydney Morning Herald

Page 108 of 129